Thoughts On The Airbus A 390

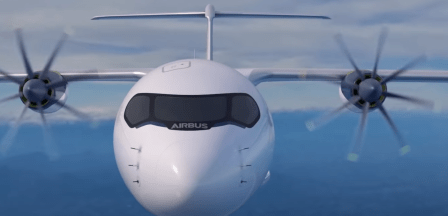

Ask Google what she knows about the Airbus A 390 and you get this AI Summary.

The Airbus A390 is a three-deck, six-engine aircraft that can carry around 1,000 passengers. It’s based on the A380, but with a third deck and extra engines. The A390 was custom-built for Qantas to fly between Melbourne and New York.

Google got their summary from this page on steemit.

Search for images of the Airbus A 390 and you get several images of this unusual three-deck aircraft, that looks like a widened Airbus A 380 with six engines.

These are some of my thoughts.

Wikipedia Entries

There is no Wikipedia entry for the Airbus A 390.

But.

- There is a Wikipedia entry for the Airbus A 380.

- There is also a Wikipedia entry for the six unusual Airbus Beluga XLs, which are used to transport two pairs of Airbus A 350 wings between factories.

The A 390 is supposedly based on the A 380 and the Beluga XL appears to have a fuselage that is a bit like the Airbus A 390.

Will The Airbus A 390 Fly?

After reading the two Wikipedia entries, I am fairly sure that an Airbus A 390 airliner, as shown in the pictures would be able to fly.

Although, I must say, that I was surprised, at seeing an Airbus Beluga XL on video. This is a Beluga XL landing at Heathrow.

So I think we can say, that Airbus know more than a bit about the aerodynamics of three-deck fuselages.

The Antonov An-225 Mriya

This aircraft designed and built in the Soviet Union , does have a Wikipedia entry.

These three paragraphs from the start of the entry, give some details of this unusual and very large aircraft.

The Antonov An-225 Mriya (Ukrainian: Антонов Ан-225 Мрія, lit. ’dream’ or ‘inspiration’) was a strategic airlift cargo aircraft designed and produced by the Antonov Design Bureau in the Soviet Union.

It was originally developed during the 1980s as an enlarged derivative of the Antonov An-124 airlifter for transporting Buran spacecraft. On 21 December 1988, the An-225 performed its maiden flight; only one aircraft was ever completed, although a second airframe with a slightly different configuration was partially built. After a brief period of use in the Soviet space programme, the aircraft was mothballed during the early 1990s. Towards the turn of the century, it was decided to refurbish the An-225 and reintroduce it for commercial operations, carrying oversized payloads for the operator Antonov Airlines. Multiple announcements were made regarding the potential completion of the second airframe, though its construction largely remained on hold due to a lack of funding. By 2009, it had reportedly been brought up to 60–70% completion.

With a maximum takeoff weight of 640 tonnes (705 short tons), the An-225 held several records, including heaviest aircraft ever built and largest wingspan of any operational aircraft. It was commonly used to transport objects once thought impossible to move by air, such as 130-ton generators, wind turbine blades, and diesel locomotives.

This further paragraph described the destruction of the aircraft.

The only completed An-225 was destroyed in the Battle of Antonov Airport in 2022 during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced plans to complete the second An-225 to replace the destroyed aircraft.

I feel that the Mriya is significant for the Airbus A 390 for three reasons.

- Mriya was a six-engine heavy-lift cargo aircraft developed from a certified four-engine transport.

- Mriya was starting to make a name for being able to move over-sized cargo around the world.

- Given the parlous state of parts of the world and the ambitions of some of its so-called leaders, I believe, as I suspect others do, that a heavy-lift cargo aircraft is needed for disaster relief.

So are Airbus looking at the possibilities of converting some unwanted A 380 airliners into the heavy-lift aircraft, that they believe the world needs?

- They may even want some for their own purposes.

- Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk may need a heavy-lift aircraft for their space programs.

Converting some unwanted Airbus A 380s into heavy-lift cargo aircraft could be a more affordable route, than designing and building new aircraft from scratch.

The Best Plane That Looks Like An Egg

The title of this post is the same as that of this article on interesting Engineering.

This is the sub-heading.

Celera 500L: Redefining aviation with its unique egg-shaped design, unparalleled fuel efficiency, and affordability.

These are the first two paragraphs.

In the world of aviation, where innovation meets the boundless sky, a groundbreaking aircraft is poised to redefine the future of air travel. Meet the Celera 500L, the brainchild of the Otto Aviation Group, an aircraft that not only boasts a distinctive egg-shaped design but also promises to transform the way we think about flying. Set to enter production in 2025, the Celera 500L is a testament to cutting-edge technology and forward-thinking design, promising to make air travel more cost-effective and eco-friendly than ever before.

One cannot help but be captivated by the Celera 500L’s futuristic aesthetics. Its unmistakable egg-shaped design is a departure from the traditional aircraft we’ve grown accustomed to seeing in the skies. However, this unique shape is not just for show; it’s the result of meticulous engineering aimed at reducing drag and maximizing efficiency.

I suggest you read the article and look at Interesting Engineering’s video.

After that have a good look at Otto Aviation’s web site.

Brief details of the business aircraft version are scattered through the pages.

- Passengers – 6

- Range – 5,000 miles

- Fuel-consumption – 33 miles per gallon.

- Power – Single pusher diesel engine.

The Otto Aviation web site, explains how it is done using laminar flow and advanced aerodynamics.

There is also this page on the ZeroAvia web site, which is entitled ZeroAvia & Otto Aviation Partner to Deliver First New Airframe Design with Hydrogen-Electric Engine Option.

Is a new world of aviation emerging?

Introducing JetZero

The Times today has an article which is entitled Up, Up And Away On An Eco-Friendly, Blended-Wing Jet.

This is the sub-heading.

The US air force hopes that a $235 million contract for a radical new design will take off

The article goes on to give a good history of blended wing bodies, before describing JetZero’s blended-wing jet and the company’s deal with the US Air Force.

More on the aircraft is available on the company’s web site. Take a look at the WHY JETZERO page.

In ZEROe – Towards The World’s First Zero-Emission Commercial Aircraft, I describe Airbus’s ZEROe BWB, which is another proposed blended wing body.

Electra.aero

I have signed up to FutureFlight‘s weekly newsletter and this week it gave two articles about a new nine-seat airliner called an Electra.aero.

It must be the first airliner named after its web site or vice-versa.

The first article is entitled Electra.aero Gives A Glimpse If Its eSTOL Technology Development Aircraft.

It says this about the aircraft and the company.

As it works on plans for a nine-passenger eSTOL blown-wing aircraft, Electra.aero has posted a short video teasing followers with a glimpse of what it describes as a technology demonstrator. The video shows what appears to be a subscale model of the larger hybrid-electric design, but the Virginia-based company is giving very little away for now.

This week, the U.S. start-up announced the appointment of former Boeing Commercial Airplanes president and CEO James Albaugh to its board of advisors, along with the former Airbus America CEO and FAA Administrator Allan McArtor, and aircraft finance expert Kristen Bartok Touw.

You can also watch a video.

The second article is entitled Electra.aero Uses Truck To Test Gives A Glimpse If Its eSTOL Aircraft Propulsion System And Wing.

It says about more the aircraft.

Electra.aero’s planned nine-passenger eSTOL aircraft is expected to be able to operate from landing strips as short as 300 feet. The company’s blown-wing design and hybrid-electric propulsion system will be key factors in achieving this breakthrough performance for regional air services. At its base in Manassas Regional Airport in Virginia, the company is using a technology demonstrator and a truck to conduct ground testing key systems in preparation for anticipated test flights later this year.

You can also watch a video.

The home page also shows a visualisation of a flight between Washington DC and New York.

Note.

- Blown-wing and blown flaps have been used before on aircraft like the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, the Boeing C-17 Globemaster and the Blackburn Buccaneer.

- Blown flaps’ use on the Electra.aero, seems to be the first application on a small propeller-driver airliner.

- Electra.aero seems well-connected, which helps in the aviation industry.

- Power seems to come from a hybrid-electric design.

- Being able to operate from landing strips as short as a football field is a unique characteristic.

- Pictures on the web site show the aircraft has eight propellers, with those close to the fuselage being larger.

- A 400 nautical mile range with a 45 minute reserve, a cruise speed of 175 knots and a quiet take-off are claimed.

As someone, who has over a thousand hours in command of a twin-engined Cessna 340A, this aircraft could be the real deal.

- The field performance is sensational.

- The range is excellent.

- Except for the number of electric engines, it looks like an aircraft and won’t put off the passengers.

- It could fly between Washington DC and New York or London and Paris.

According to their web site, they already have a $3 billion order-book.

Zero-Carbon Emission Flights To Anywhere In The World Possible With Just One Stop

The title of this post, is the same as that of this press release from the Aerospace Technology Institute.

This is the first sentence of the press release.

Passengers could one day fly anywhere in the world with no carbon emissions and just one stop on board a concept aircraft unveiled by the Aerospace Technology Institute (ATI) today.

These three paragraphs describe the concept.

Up to 279 passengers could fly between London and San Francisco, USA direct or Auckland, New Zealand with just one stop with the same speed and comfort as today’s aircraft, revolutionising the future of air travel.

Developed by a team of aerospace and aviation experts from across the UK collaborating on the government backed FlyZero project, the concept demonstrates the huge potential of green liquid hydrogen for air travel not just regionally or in short haul flight but for global connectivity. Liquid hydrogen is a lightweight fuel, which has three times the energy of kerosene and sixty times the energy of batteries per kilogramme and emits no CO2 when burned.

Realising a larger, longer range aircraft also allows the concentration of new infrastructure to fewer international airports accelerating the rollout of a global network of zero-carbon emission flights and tackling emissions from long haul flights.

These are my thoughts.

The Airframe

This picture downloaded from the Aerospace Technology Institute web site is a visualisation of their Fly Anywhere Aircraft.

Some features stand out.

The wings are long, narrow and thin, almost like those of a sailplane. High aspect ratio wings like these offer more lift and stability at high altitude, so will the plane fly higher than the 41,000-43,000 feet of an Airbus A350?

I wouldn’t be surprised if it does, as the higher you go, the thinner the air and the less fuel you will burn to maintain speed and altitude.

The horizontal stabiliser is also small as this will reduce drag and better balance with the wing.

The tailfin also appears small for drag reduction.

The body is bloated compared to say an Airbus A 350 or a Boeing 777. Could this be to provide space for the liquid hydrogen, which can’t be stored in the thin wings?

The fuselage also appears to be a lifting body, with the wings blended into the fat body. I suspect that the hydrogen is carried in this part of the fuselage, which would be about the centre of lift of the aeroplane.

The design of the airframe appears to be all about the following.

- Low drag.

- high lift and stability.

- Large internal capacity to hold the liquid hydrogen.

It may just look fat, but it could be as radical as the first Boeing 747 was in 1969.

The Engines

I suspect the engines will be developments of current engines like the Rolls-Royce Trent XWB, which will be modified to run on hydrogen.

If they are modified Trent engines, it will be astonishing to think, that these engines can be traced in an unbroken line to the RB211, which was first run in 1969.

The Flight Controls

Most airliners these days and certainly all those built by Airbus have sophisticated computer control systems and this plane will take them to another level.

The Flight Profile

If you want to fly any aircraft a long distance, you generally climb to a high level fairly quickly and then fly straight and level, before timing the descent so you land at the destination with as small amount of fuel as is safe, to allow a diversion to another airport.

I once flew from Southend to Naples in a Cessna 340.

- I made sure that the tanks were filled to the brim with fuel.

- I climbed to a high altitude as I left Southend Airport.

- For the journey across France I asked for and was given a transit at Flight Level 195 (19,500 feet), which was all legal in France under visual flight rules.

- When the French handed me over to the Italians, legally I should have descended, but the Italians thought I’d been happy across France at FL195, so they didn’t bother to ask me to descend.

- I flew down the West Coast of Italy at the same height, with an airspeed of 185 knots (213 mph)

- I was then vectored into Naples Airport by radar.

I remember the flight of 981 miles took around six hours. That is an average of 163.5 mph.

I would expect the proposed aircraft would fly a similar profile, but the high level cruise would be somewhere above the 41,000-43,000 feet of an Airbus A 350. We must have a lot of data about flying higher as Concorde flew at 60,000 feet and some military aircraft fly at over 80,000 feet.

The press release talks about London to San Francisco, which is a distance of 5368 miles.

This aircraft wouldn’t sell unless it was able to beat current flight time of eleven hours and five minutes on that route.

Ground Handling

When the Boeing 747 started flying in the 1970s, size was a big problem and this aircraft with its long wing may need modifications to runways, taxiways and terminals.

Passenger Capacity

The press release states that the capacity of the aircraft will be 279 passengers, as against the 315 and 369 passengers of the two versions of the A 350.

So will there be more flights carrying less passengers?

Liquid Hydrogen Refuelling

NASA were doing this successfully in the 1960s for Saturn rockets and the Space Shuttle.

Conclusion

This aircraft is feasible.

A Selection Of Train Noses

I have put together a selection of pictures of train noses.

They are in order of introduction into service.

Class 43 Locomotive

The nose of a Class 43 locomotive was designed by Sir Kenneth Grange.

Various articles on the Internet, say that he thought British Rail’s original design was ugly and that he used the wind tunnel at Imperial College to produce one of the world’s most recognised train noses.

- He tipped the lab technician a fiver for help in using the tunnel

- Pilkington came had developed large armoured glass windows, which allowed the locomotives window for two crew.

- He suggested that British Rail removed the buffers. Did that improve the aerodynamics, with the chisel nose shown in the pictures?

The fiver must be one of the best spent, in the history of train design.

In How Much Power Is Needed To Run A Train At 125 mph?, I did a simple calculation using these assumptions.

- To cruise at 125 mph needs both engines running flat out producing 3,400 kW.

- Two locomotives and eight Mark 3 carriages are a ten-car InterCity 125 train.

This means that the train needs 2.83 kWh per vehicle mile.

Class 91 Locomotive

These pictures show the nose of a Class 91 locomotive.

Note, the Class 43 locomotive for comparison and that the Driving Van Trailers have an identical body shell.

It does seem to me, that looking closely at both locomotives and the driving van trailers, that the Class 43s look to have a smoother and more aerodynamic shape.

Class 800/801/802 Train

These pictures show the nose of a Class 800 train.

In How Much Power Is Needed To Run A Train At 125 mph?, I did a simple calculation to find out the energy consumption of a Class 801 train.

I have found this on this page on the RailUKForums web site.

A 130m Electric IEP Unit on a journey from Kings Cross to Newcastle under the conditions defined in Annex B shall consume no more than 4600kWh.

This is a Class 801 train.

- It has five cars.

- Kings Cross to Newcastle is 268.6 miles.

- Most of this journey will be at 125 mph.

- The trains have regenerative braking.

- I don’t know how many stops are included

This gives a usage figure of 3.42 kWh per vehicle mile.

It is a surprising answer, as it could be a higher energy consumption, than that of the InterCity 125.

I should say that I don’t fully trust my calculations, but I’m fairly sure that the energy use of both an Intercity 125 and a Class 801 train are in the region of 3 kWh per vehicle mile.

Class 717 Train

Aerodynamically, the Class 700, 707 and 717 trains have the same front.

But they do seem to be rather upright!

Class 710 Train

This group of pictures show a Class 710 train.

Could these Aventra trains have been designed around improved aerodynamics?

- They certainly have a more-raked windscreen than the Class 717 train.

- The cab may be narrower than the major part of the train.

- The headlights and windscreen seem to be fared into the cab, just as Colin Chapman and other car designers would have done.

- There seems to be sculpting of the side of the nose, to promote better laminar flow around the cab. Does this cut turbulence and the energy needed to power the train?

- Bombardier make aircraft and must have some good aerodynamicists and access to wind tunnels big enough for a large scale model of an Aventra cab.

If you get up close to the cab, as I did at Gospel Oak station, it seems to me that Bombardier have taken great care to create a cab, that is a compromise between efficient aerodynamics and good visibility for the driver.

Class 345 Train

These pictures shows the cab of a Class 345 train.

The two Aventras seem to be very similar.

Class 195 And Class 331 Trains

CAF’s Class 195 and Class 331 trains appear to have identical noses.

They seem to be more upright than the Aventras.

Class 755 Train

Class 755 trains are Stadler’s 100 mph bi-mode trains.

It is surprising how they seem to follow similar designs to Bombardier’s Aventras.

- The recessed windscreen.

- The large air intake at the front.

I can’t wait to get a picture of a Class 755 train alongside one of Greater Anglia’s new Class 720 trains, which are Aventras.

Thoughts On The Aerodynamics Of A Class 91 Locomotive

The Class 91 locomotive is unique in that it the only UK locomotive that has a pointed and a blunt end.

The Wikipedia entry has external and internal pictures of both cabs, which are both fully functional.

The speeds of the locomotive are given as follows.

- Design – 140 mph

- Service – 125 mph

- Record – 161.7 mph

- Running blunt end first – 110 mph

The aerodynamic drag of the train is determined by several factors.

- The quality of the aerodynamic design.

- The cross-sectional area of the train.

- The square of the speed.

- The power available.

The maximum speed on a level track, will probably be determined when the power available balances the aerodynamic force on the front of the train.

But with a train or an aircraft, you wouldn’t run it on the limit, but at a safe lower service speed, where all the forces were calm and smooth.

If you compare normal and blunt end first running, the following can be said.

- The cross sectional area is the same.

- The available power is the same.

- Power = DragCoefficient * Speed*Speed, where the DragCoefficient is a rough scientifically-incorrect coefficient.

So I can formulate this equation.

DragCoefficientNormal * 125*125 = DragCoefficientBlunt * 110*110

Solving this equation shows that the drag coefficient running blunt end first is twenty-nine percent higher, than when running normally.

Looking at the front of a Class 91 locomotive and comparing it with its predecessor the Class 43 locomotive, it has all the subtlety of a brick.

The design is a disgrace.

Conclusion

This crude analysis shows the importance of good aerodynamic design, in all vehicles from bicycles to fifty tonne trucks.

If