Could Doncaster Sheffield Airport Become A Hydrogen Airport?

I asked Google AI, what is the current status of Doncaster Sheffield Airport and received this reply.

Doncaster Sheffield Airport (DSA) is currently in a state of active, public-funded redevelopment after closing in late 2022 due to financial issues, with plans to reopen for passenger flights by late 2027 or 2028, following significant funding (around £160m) secured by the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority (SYMCA) for the City of Doncaster Council to take over operations and rebuild commercial viability, with freight and general aviation potentially returning sooner.

This Google Map shows the location of the airport.

Note.

- The distinctive mouth of the River Humber can be picked out towards the North-East corner of the map.

- Hull and Grimsby sit in the mouth of the Humber.

- The red arrow indicates Doncaster Sheffield Airport.

- Leeds is in the North-West corner of the map.

- The towns and city of Doncaster, Rotherham and Sheffield can be picked out to the West of the airport.

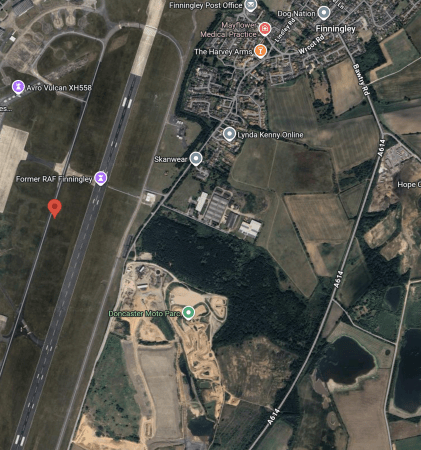

This second Google Map shows a close-up of the airport.

On my visit to NASA in the 1980s, where an Artemis system was used to project manage the turnround of the Space Shuttle, I was asked questions by one of NASA’s support people about RAF Finningley. Nothing too technical, but things like what is Doncaster like.

When I asked why, they said there’s a high chance that a Space Shuttle could land at RAF Finningley, as it has one of the best runways for a very heavy aircraft in Europe.

Looking at the runway, it is a long and wide runway that was built for heavy RAF nuclear bombers like Valiants, Victors and Vulcans.

I believe that we will eventually see hydrogen- and/or nuclear-powered airliners flying very long routes across the globe, just as a nuclear-powered example, attempted to do in the first episode of the TV series Thunderbirds, which was called Trapped in the Sky and has this Wikipedia entry.

Just as the Space Shuttle did, these airliners and their air-cargo siblings will need a large runway.

Doncaster Sheffield Airport already has such a runway.

These hydrogen- and nuclear-powered aircraft will make Airbus A 380s look small and will need runways like the one at Finningley.

But I don’t think we’ll ever see nuclear-powered aircraft in the near future, so the aircraft will likely be hydrogen.

Other things in favour of making Doncaster Sheffield Airport, an airport for long range hydrogen aircraft include.

- The airport is close to the massive hydrogen production and storage facilities being developed on Humberside at Aldbrough and Rough.

- The airport could be connected to the Sheffield Supertram.

- The airport could be connected to the trains at Doncaster station, which has 173 express trains per day to all over the country.

- The airport would fit well with my thoughts on hydrogen-powered coaches, that I wrote about inFirstGroup Adds Leeds-based J&B Travel To Growing Coach Portfolio

- The airport might even be able to accept the next generation of supersonic aircraft.

- The airport could certainly accept the largest hydrogen-powered cargo aircraft.

- The Airport isn’t far from Doncaster iPort railfreight terminal.

Did I read too much science fiction?

I have some further thoughts.

Do Electric Aircraft Have A Future?

I asked Google AI this question and received this answer.

Yes, electric aircraft absolutely have a future, especially for short-haul, regional, and urban air mobility (UAM), promising quieter, zero-emission flights, but battery limitations mean long-haul flights will rely more on hydrogen-electric or Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) for the foreseeable future. Expect to see battery-electric planes for shorter trips by the late 2020s, while hybrid or hydrogen solutions tackle longer distances, with a significant shift towards alternative propulsion by 2050.

That doesn’t seem very promising, so I asked Google AI what range can be elected from electric aircraft by 2035 and received this answer.

By 2035, fully electric aircraft ranges are expected to be around 200-400 km (125-250 miles) for small commuter planes, while hybrid-electric models could reach 800-1,000 km (500-620 miles), focusing on short-haul routes due to battery limitations; larger, long-range electric flight remains decades away, with hydrogen propulsion targeting 1,000-2,000 km ranges for that timeframe.

Note.

- I doubt that many prospective passengers would want to use small commuter planes for up to 250 miles from Doncaster Sheffield airport with hundreds of express trains per day going all over the UK mainland from Doncaster station.

- But Belfast City (212 miles), Dublin (215 miles) and Ostend (227 miles), Ronaldsway on the Isle of Man (154 miles) and Rotterdam(251 miles) and Schipol 340 miles) may be another matter, as there is water to cross.

It looks like it will be after 2035 before zero-carbon aircraft will be travelling further than 620 miles.

My bets would be on these aircraft being hydrogen hybrid aircraft.

What Will The Range Of Hydrogen-Powered Aircraft In 2040?

I asked Google AI this question and received this answer.

By 2040, hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft are projected to have a range that covers short- to medium-haul flights, likely up to 7,000 kilometers (approximately 3,780 nautical miles), with some models potentially achieving longer ranges as technology and infrastructure mature.

The range of these aircraft will vary depending on the specific technology used (hydrogen fuel cells versus hydrogen combustion in modified gas turbines) and aircraft size.

It looks like we’ll be getting there.

This Wikipedia entry is a list of large aircraft and there are some very large aircraft, like the Antonov An-225, which was destroyed in the Ukraine War.

A future long-range hydrogen-powered airline must be able to match the range of current aircraft that will need to be replaced.

I asked Google AI what airliner has the longest range and received this reply.

The longest-range airliner in service is the Airbus A350-900ULR (Ultra Long Range), specifically configured for airlines like Singapore Airlines to fly extremely long distances, reaching around 9,700 nautical miles (18,000 km) for routes like Singapore to New York. While the A350-900ULR holds records for current operations, the upcoming Boeing 777-8X aims to compete, and the Boeing 777-200LR was previously known for its exceptional range.

I believe that based on the technology of current successful aircraft, that an aircraft could be built, that would be able to have the required range and payload to be economic, with the first version probably being a high-capacity cargo version.

What Would An Ultra Long Range Hydrogen-Powered Airliner Look Like?

Whatever the aircraft looks like it will need to be powered. Rolls-Royce, appear to be destining a future turbofan for aircraft called the Ultrafan, which has this Wikipedia entry.

I asked Google AI, if Rolls-Royce will produce an Ultrafan for hydrogen and received this answer.

Rolls-Royce is actively developing the UltraFan architecture to be compatible with hydrogen fuel in the future, but the current UltraFan demonstrator runs on Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). The company has a research program dedicated to developing hydrogen-powered engines for future aircraft, aiming for entry into service in the mid-2030s.

I asked Google AI, if Rolls-Royce have had major difficulties converting engines to hydrogen and received this answer.

Rolls-Royce has not encountered insurmountable difficulties but faces significant engineering and logistical challenges in converting engines to run on hydrogen. The company has made substantial progress in testing both stationary and aero engines using pure hydrogen, confirming its technical feasibility.

Given the company’s success in developing engines in the past, like the R Type, Merlin, RB 211, Pegasus, Trent, mtu 4000 and others, I suspect there’s a high chance of a successful hydrogen-powered Ultrafan.

If you look at a history of large passenger and cargo aircraft over the last sixty years, there has been a lot of the following.

- Conversion of one type of aircraft to a totally different type.

- Fitting new engines to a particular type.

- Fitting new avionics to a particular type.

Examples include.

- Fitting new CFM-56 engines to DC-8s.

- The first two Nimrods were converted from unsold Comet 4Cs.

- Converting Victor bombers to RAF tanker aircraft.

- Converting BA Tristars to RAF tanker aircraft.

- Converting DC-8s to cargo aircraft.

- Airbus converted five Airbus A 300-600 into Belugas, which have this Wikipedia entry.

- Airbus converted six Airbus A 330-200F into BelugaXLs, which have this Wikipedia entry.

- Converting two Boeing-747s to carry Space Shuttles ; one from American Airlines and one from Japan Airlines, which have this Wikipedia entry.

Note.

- Most of these examples have been successful.

- The last three examples have been very successful.

- Most of these applications do not have a human cargo.

This picture shows an Emirates Air Lines’s Airbus A 380 on finals at Heathrow.

Note.

- The aircraft was landing on Runway 27 L.

- The four engines and the vertical oval cross-section of the fuselage are clearly visible.

- The Wikipedia entry for the Airbus A 380 shows two floors across the fuselage; the upper floor with eight seats in 2-4-2 and the lower floor with ten seats in 3-4-3, and a pair of LD3 cargo containers in the basement.

I’d be interested to know, how much hydrogen could be put in the basement and how far it could take the plane with a full load of passengers!

This link to the Wikipedia entry, shows the cross section in detail.

Note

I wouldn’t be surprised that the first application of large hydrogen aircraft will be for cargo and it could be an Airbus Beluga or perhaps an Airbus A 380 freighter?

Should The Great Northern And Great Eastern Joint Line Be Electrified?

The Great Northern And Great Eastern Joint Line was created in the Nineteenth Century by the Great Northern Railway and the Great Eastern Railway.

- The main purpose was to move freight like coal, agricultural products and manufactured goods between Yorkshire and Eastern England.

- It originally ran between Doncaster and Huntington via Gainsborough, Lincoln, Sleaford, Spalding and March.

- It had a full length of almost 123 miles.

- There was a large marshalling yard at Whitemoor near March.

Over the years the line has been pruned a bit and now effectively runs between Doncaster and Peterborough.

- Trains between Lincoln and March are now routed via Peterborough.

- It carries upwards of twenty freight trains per day in both directions through Lincoln Central station.

- Many of the freight trains are going to and from the East Coast ports.

- The distance between Doncaster and Peterborough is 93.7 miles, as opposed to the 79.6 miles on the East Coast Main Line.

- The line is not electrified, but it connects to the electrified East Coast Main Line at both ends.

There have been some important developments in recent years.

2015 Freight Upgrade

Wikipedia says this about the major 2015 freight upgrade.

In 2015 a £280 million upgrade of the Joint Line by Network Rail was substantially complete, enabling two freight trains per hour to be diverted from the congested East Coast Main Line; gauge enhancements to enable the passage of 9 ft 6 in (2.90 m) containers were included in the work.

The Sleaford avoiding line had been substantially downgraded since the 1980s and was reinstated to double track as part of the 2015 scheme. Resignalling and modernisation of level crossings was included.

This means that freight trains have an alternative route, that avoids the East Coast Main Line.

Doncaster iPort

Over the last few years the Doncaster iPort has been developed, which is an intermodal rail terminal.

- It has a size of around 800 acres.

- The site opened in early 2018.

- There is a daily train to the Port of Southampton and two daily trains to both Teesport and Felixstowe.

- The Felixstowe trains would appear to use the Joint Line.

I feel that as the site develops, the Doncaster iPort will generate more traffic on the Joint Line.

This Google Map shows the Doncaster iPort.

There would appear to be plenty of space for expansion.

The Werrington Dive Under

The Werrington Dive Under has been built at a cost of £ 200 million, to remove a bottleneck at the Southern end of the Joint Line, where it connects to the East Coast Main Line.

The Werrington Dive Under was built, so that it could be electrified in the future.

LNER To Lincolnshire

LNER appear to have made a success of a one train per two hours (tp2h) service between London King’s Cross and Lincoln station.

- LNER have stated, that they want to serve Grimsby and Cleethorpes in the North of the county.

- North Lincolnshire is becoming important in supporting the wind energy industry in the North Sea.

- Lincoln is becoming an important university city.

- Several towns in Lincolnshire probably need a service to Peterborough and London.

- In 2019, the Port of Grimsby & Immingham was the largest port in the United Kingdom by tonnage.

I can see an expanded Lincolnshire service from LNER.

Full Digital Signalling Of The East Coast Main Line To The South Of Doncaster

This is happening now and it will have a collateral benefits for the Joint Line.

Most passenger and freight trains will also use the East Coast Main Line, if only for a few miles, which will mean they will need to be fitted for the digital signalling.

This could mean that extending full digital signalling to Lincolnshire will not be a challenging project.

Arguments For Electrification

These are possible arguments for electrification.

Electric Freight Trains To And From The North

It would be another stretch of line, that could accommodate electric freight trains.

An Electrified Diversion Route For East Coast Main Line Expresses

Currently, when there is engineering blockades between Doncaster and Peterborough on the East Coast Main Line, the Hitachi Class 800 and Class 802 trains of Hull Trains and LNER are able to divert using their diesel power.

But the electric trains of LNER and Lumo have to be cancelled.

An electrified diversion route would be welcomed by passengers and train companies.

It would also mean that any trains running from King’s Cross to electrified destinations would not to have any diesel engines.

An Electrified Spine Through Lincolnshire

If there was an electrified spine between Doncaster and Peterborough via Gainsborough, Lincoln, Sleaford and Spalding, these stations would be these distances from the spine.

- Boston – 16.8 miles

- Cleethorpes – 47.2 miles

- Grimsby Town – 43.9 miles

- Market Rasen – 14.8 miles

- Skegness – 40.7 miles

Note.

- These distances are all possible with battery-electric trains.

- Charging would be on the electrified spine and at Skegness and Cleethorpes stations.

All of South Lincolnshire and services to Doncaster would use electric trains.

London Services

London services would be via Spalding and join the East Coast Main Line at Werrington.

- Boston and Skegness would be served from Sleaford, where the train would reverse.

- Market Rasen, Grimsby Town and Cleethorpes would be served from Lincoln, where the train would reverse.

This would enable Cleethorpes and Skegness to have at least four trains per day to and from London King’s Cross.

North Lincolnshire Services

There are two train services in North Lincolnshire.

Cleethorpes and Barton-on-Humber.

Cleethorpes and Manchester Airport via Grimsby Town, Scunthorpe, Doncaster, Sheffield and Manchester Piccadilly.

Note.

- Cleethorpes would need to have a charger or a few miles of electrification, to charge a train from London.

- Doncaster, which is fully electrified is 52.1 miles from Cleethorpes.

- Barton-on-Humber is 22.8 miles from Cleethorpes.

Battery-electric trains should be able to handle both services.

Arguments Against Electrification

The only possible arguments against electrification are the disruption that the installation might cause and the unsightly nature of overhead gantries.

Conclusion

The Great Northern and Great Eastern Joint Line should be electrified.

Beeching Reversal – South Yorkshire Joint Railway

This is one of the Beeching Reversal projects that the Government and Network Rail are proposing to reverse some of the Beeching cuts.

This railway seems to have been forgotten, as even Wikipedia only has a rather thin entry for the South Yorkshire Joint Railway.

The best description of the railway, that I’ve found is from this article in the Doncaster Free Press, which is entitled South Yorkshire Railway Line, Which Last Carried Passengers 100 Years Ago Could Be Reopened.

This is said.

The line remains intact, and recently maintained, runs from Worksop through to Doncaster, via North and South Anston, Laughton Common/Dinnington and Maltby.

I jave got my helicopter out and navigating with the help of Wikipedia, I have traced the route of the South Yorkshire Joint Railway (SYJR) between Worksop and Doncaster.

Shireoaks Station

This Google Map shows the Southern end of the SYJR on the Sheffield and Gainsborough Central Line between Shireoaks and Kiveton Park stations.

Note.

- Shireoaks station is in the East.

- Kiveton Park station is in the West.

- The SYJR starts at the triangular junction in the middle of the map.

- Lindrick Golf Club, where GB & NI, won the Ryder Cup in 1957 is shown by a green arrow to the North of Shireoaks station.

- The original passenger service on the SYJR, which closed in the 1920s, appears to have terminated at Shireoaks station.

The line immediately turns West and then appears to run between the villages of North and South Anston.

Anston Station

This Google Map shows the location of Anston station.

Note that the SYJR goes between the two villages and runs along the North side of the wood, that is to the North of Worksop Road.

Dinnington & Laughton Station

This Google Map shows the location of the former Dinnington & Laughton station.

Note that the SYJR goes to the west side of both villages, so it would have been quite a walk to the train.

Maltby Station

This Google Map shows the location of the former Maltby station.

Note.

- The SYJR goes around the South side of the village.

- The remains of the massive Maltby Main Colliery, which closed several years ago.

I wonder if they fill the shafts of old mines like this. if they don’t and just cap them, they could be used by Gravitricity to store energy. In Explaining Gravitricity, I do a rough calculation of the energy storage with a practical thousand tonne weight. Maltby Main’s two shafts were 984 and 991 metres deep. They would store 2.68 and 2.70 MWh respectively.

It should be noted that Gravitricity are serious about 5.000 tonnes weights.

Tickhill & Wadworth Station

This Google Map shows the location of the former Tickhill & Wadworth station.

Note.

- Tickhill is in the South and Wadworth is in the North.

- Both villages are to the West of the A1 (M)

- The SYJR runs in a North-Easterly direction between the villages.

The station appears to have been, where the minor road and the railway cross.

Doncaster iPort

The SYJR then passes through Doncaster iPort.

Note.

- The iPort seems to be doing a lot of work for Amazon.

- The motorway junction is Junction 3 on the M18.

- The SYJR runs North-South on the Western side of the centre block of warehouses.

This is Wikipedia’s introductory description of the iPort.

Doncaster iPort or Doncaster Inland Port is an intermodal rail terminal; a Strategic Rail Freight Interchange, under construction in Rossington, Doncaster at junction 3 of the M18 motorway in England. It is to be connected to the rail network via the line of the former South Yorkshire Joint Railway, and from an extension of the former Rossington Colliery branch from the East Coast Main Line.

The development includes a 171-hectare (420-acre) intermodal rail terminal to be built on green belt land, of which over 50 hectares (120 acres) was to be developed into warehousing, making it the largest rail terminal in Yorkshire; the development also included over 150 hectares (370 acres) of countryside, the majority of which was to remain in agricultural use, with other parts used for landscaping, and habitat creation as part of environment mitigation measures.

It ;looks like the SYJR will be integrated with the warehouses, so goods can be handled by rail.

Onward To Doncaster

After the iPort, the trains can take a variety of routes, some of which go through Doncaster station.

I have some thoughts on the South Yorkshire Joint Railway (SYJR).

Should The Line Be Electrified?

This is always a tricky one, but as there could be a string of freight trains running between Doncaster iPort and Felixstowe, something should be done to cut the carbon emissions and pollution of large diesel locomotives.

Obviously, one way to sort out Felixstowe’s problem, would be to fill in the gaps of East Anglian electrification and to electrify the Great Northern and Great Eastern Joint Line between Peterborough and Doncaster via Lincoln. But I suspect Lincolnshire might object to up to fifteen freight trains per hour rushing through. Even, if they were electric!

I am coming round to the believe that Steamology Motion may have a technology, that could haul a freight train for a couple of hours.

These proposed locomotives, which are fuelled by hydrogen and oxygen, will have an electric transmission and could benefit from sections of electrification, which could power the locomotives directly.

So sections of electrification along the route, might enable the freight trains to go between Felixstowe and Doncaster iPort without using diesel.

It should be said, that Steamology Motion is the only technology, that I’ve seen, that has a chance of converting a 3-4 MW diesel locomotive to zero carbon emissions.

Many think it is so far-fetched, that they’ll never make it work!

Electrification of the line would also enable the service between Doncaster and Worksop to be run by Class 399 tram-trains, which are pencilled in to be used to the nearby Doncaster Sheffield Airport.

What Rolling Stock Should Be Used?

As I said in the previous section, I feel that Class 399 tram-trains would be ideal, if the line were to be electrified.

Also, if the line between Shireoaks and Kiveton Park stations were to be electrified to Sheffield, this would connect the South Yorkshire Joint Line to Sheffield’s Supertram network.

Surely, one compatible tram-train type across South Yorkshire, would speed up development of a quality public transport system.

A service could also be run using Vivarail’s Pop-up Metro concept, with fast charging at one or two, of any number of the stations.

Conclusion

This seems to be a worthwhile scheme, but I would like to see more thought on electrification of the important routes from Felixstowe and a unified and very extensive tram-train network around Sheffield.