Will Hitachi Announce A High Speed Metro Train?

As the UK high speed rail network increases, we are seeing more services and proposed services, where local services are sharing tracks, where trains will be running at 125 mph or even more.

London Kings Cross And Cambridge/Kings Lynn

This Great Northern service is run by Class 387 trains.

- Services run between London Kings Cross and King’s Lynn or Cambridge

- The Class 387 trains have a maximum operating speed of 110 mph.

- The route is fully electrified.

- The trains generally use the fast lines on the East Coast Main Line, South of Hitchin.

- Most trains on the fast lines on the East Coast Main Line are travelling at 125 mph.

When in the future full digital in-cab ERTMS signalling is implemented on the East Coast Main Line, speeds of up to 140 mph should be possible in some sections between London Kings Cross and Hitchin.

The Digswell Viaduct Problem

I also believe that digital signalling may be able to provide a solution to the twin-track bottleneck over the Digswell Viaduct.

Consider.

- Airliners have been flown automatically and safely from airport to airport for perhaps four decades.

- The Victoria Line in London, has been running automatically and safely at over twenty trains per hour (tph) for five decades. It is now running at over 30 tph.

- I worked with engineers developing a high-frequency sequence control system for a complicated chemical plant in 1970.

We also can’t deny that computers are getting better and more capable.

For these reasons, I believe there could be an ERTMS-based solution to the problem of the Digswell Viaduct, which could be something like this.

- All trains running on the two track section over the Digswell Viaduct and through Welwyn North station would be under computer control between Welwyn Garden City and Knebworth stations.

- Fast trains would be slowed as appropriate to create spaces to allow the slow trains to pass through the section.

- The train drivers would be monitoring the computer control, just as they do on the Victoria Line.

Much more complicated automated systems have been created in various applications.

The nearest rail application in the UK, is probably the application of digital signalling to London Underground’s Circle, District, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan Lines.

This is known at the Four Lines Modernisation and it will be completed by 2023 and increase capacity by up to twenty-seven percent.

I don’t think it unreasonable to see the following maximum numbers of services running over the Digswell Viaduct by 2030 in both directions in every hour.

- Sixteen fast trains

- Four slow trains

That is one train every three minutes.

Currently, it appears to be about ten fast and two slow.

As someone, who doesn’t like to be on a platform, when a fast train goes through, I believe that some form of advanced safety measures should be installed at Welwyn North station.

It would appear that trains between London Kings Cross and King’s Lynn need to have this specification.

- Ability to run at 125 mph on the East Coast Main Line

- Ability to run at 140 mph on the East Coast Main Line, under control of full digital in-cab ERTMS signalling.

This speed increase could reduce the journey time between London Kings Cross and Cambridge to just over half-an-hour with London Kings Cross and King’s Lynn under ninety minutes.

The only new infrastructure needed would be improvements to the Fen Line to King’s Lynn to allow two tph, which I think is needed.

Speed improvements between Hitchin and Cambridge could also benefit timings.

London Kings Cross And Cambridge/Norwich

I believe there is a need for a high speed service between London Kings Cross and Norwich via Cambridge.

- The Class 755 trains, that are capable of 100 mph take 82 minutes, between Cambridge and Norwich.

- The electrification gap between Ely and Norwich is 54 miles.

- Norwich station and South of Ely is fully electrified.

- Greater Anglia’s Norwich and Cambridge service has been very successful.

With the growth of Cambridge and its incessant need for more space, housing and workers, a high speed train between London Kings Cross and Norwich via Cambridge could tick a lot of boxes.

- If hourly, it would double the frequency between Cambridge and Norwich until East-West Rail is completed.

- All stations between Ely and Norwich get a direct London service.

- Cambridge would have better links for commuting to the city.

- Norwich would provide the quality premises, that Cambridge is finding hard to develop.

- London Kings Cross and Cambridge would be just over half an hour apart.

- If the current London Kings Cross and Ely service were to be extended to Norwich, no extra paths on the East Coast Main Line would be needed.

- Trains could even split and join at Cambridge or Ely to give all stations a two tph service to London Kings Cross.

- No new infrastructure would be required.

The Cambridge Cruiser would become the Cambridge High Speed Cruiser.

London Paddington And Bedwyn

This Great Western Railway service is run by Class 802 trains.

- Services run between London Paddington and Bedwyn.

- Services use the Great Western Main Line at speeds of up to 125 mph.

- In the future if full digital in-cab ERTMS signalling is implemented, speeds of up to 140 mph could be possible on some sections between London Paddington and Reading.

- The 13.3 miles between Newbury and Bedwyn is not electrified.

As the service would need to be able to run both ways between Newbury and Bedwyn, a capability to run upwards of perhaps thirty miles without electrification is needed. Currently, diesel power is used, but battery power would be better.

London Paddington And Oxford

This Great Western Railway service is run by Class 802 trains.

- Services run between London Paddington and Oxford.

- Services use the Great Western Main Line at speeds of up to 125 mph.

- In the future if full digital in-cab ERTMS signalling is implemented, speeds of up to 140 mph could be possible on some sections between London Paddington and Didcot Parkway.

- The 10.3 miles between Didcot Parkway and Oxford is not electrified.

As the service would need to be able to run both ways between Didcot Parkway and Oxford, a capability to run upwards of perhaps thirty miles without electrification is needed. Currently, diesel power is used, but battery power would be better.

Local And Regional Trains On Existing 125 mph Lines

In The UK, in addition to High Speed One and High Speed Two, we have the following lines, where speeds of 125 mph are possible.

- East Coast Main Line

- Great Western Main Line

- Midland Main Line

- West Coast Main Line

Note.

- Long stretches of these routes allow speeds of up to 125 mph.

- Full digital in-cab ERTMS signalling is being installed on the East Coast Main Line to allow running up to 140 mph.

- Some of these routes have four tracks, with pairs of slow and fast lines, but there are sections with only two tracks.

It is likely, that by the end of the decade large sections of these four 125 mph lines will have been upgraded, to allow faster running.

If you have Hitachi and other trains thundering along at 140 mph, you don’t want dawdlers, at 100 mph or less, on the same tracks.

These are a few examples of slow trains, that use two-track sections of 125 nph lines.

- East Midlands Railway – 1 tph – Leicester and Lincoln – Uses Midland Main Line

- East Midlands Railway – 1 tph – Liverpool and Norwich – Uses Midland Main Line

- East Midlands Railway – 2 tph – St. Pancras and Corby – Uses Midland Main Line

- Great Western Railway – 1 tph – Cardiff and Portsmouth Harbour – Uses Great Western Main Line

- Great Western Railway – 1 tph – Cardiff and Taunton – Uses Great Western Main Line

- Northern – 1 tph – Manchester Airport and Cumbria – Uses West Coast Main Line

- Northern – 1 tph – Newcastle and Morpeth – Uses East Coast Main Line

- West Midlands Trains – Some services use West Coast Main Line.

Conflicts can probably be avoided by judicious train planning in some cases, but in some cases trains capable of 125 mph will be needed.

Southeastern Highspeed Services

Class 395 trains have been running Southeastern Highspeed local services since 2009.

- Services run between London St. Pancras and Kent.

- Services use Speed One at speeds of up to 140 mph.

- These services are planned to be extended to Hastings and possibly Eastbourne.

The extension would need the ability to run on the Marshlink Line, which is an electrification gap of 25.4 miles, between Ashford and Ore.

Thameslink

Thameslink is a tricky problem.

These services run on the double-track section of the East Coast Main Line over the Digswell Viaduct.

- 2 tph – Cambridge and Brighton – Fast train stopping at Hitchin, Stevenage and Finsbury Park.

- 2 tph – Cambridge and Kings Cross – Slow train stopping at Hitchin, Stevenage, Knebworth, Welwyn North, Welwyn Garden City, Hatfield, Potters Bar and Finsbury Park

- 2 tph – Peterborough and Horsham – Fast train stopping at Hitchin, Stevenage and Finsbury Park.

Note.

- These services are run by Class 700 trains, that are only capable of 100 mph.

- The fast services take the fast lines South of the Digswell Viaduct.

- South of Finsbury Park, both fast services cross over to access the Canal Tunnel for St, Pancras station.

- I am fairly certain, that I have been on InterCity 125 trains running in excess of 100 mph in places between Finsbury Park and Stevenage.

It would appear that the slow Thameslink trains are slowing express services South of Stevenage.

As I indicated earlier, I think it is likely that the Kings Cross and King’s Lynn services will use 125 mph trains for various reasons, like London and Cambridge in under half an hour.

But if 125 mph trains are better for King’s Lynn services, then they would surely improve Thameslink and increase capacity between London and Stevenage.

Looking at average speeds and timings on the 25 miles between Stevenage and Finsbury Park gives the following.

- 100 mph – 15 minutes

- 110 mph – 14 minutes

- 125 mph – 12 minutes

- 140 mph – 11 minutes

The figures don’t appear to indicate large savings, but when you take into account that the four tph running the Thameslink services to Peterborough and Cambridge stop at Finsbury Park and Stevenage and have to get up to speed, I feel that the 100 mph Class 700 trains are a hindrance to more and faster trains on the Southern section of the East Coast Main Line.

It should be noted, that faster trains on these Thameslink services would probably have better acceleration and and would be able to execute faster stops at stations.

There is a similar less serious problem on the Midland Main Line branch of Thameslink, in that some Thameslink services use the fast lines.

A couple of years ago, I had a very interesting chat with a group of East Midlands Railway drivers. They felt that the 100 mph Thameslink and the 125 mph Class 222 trains were not a good mix.

The Midland Main Line services are also becoming more complicated, with the new EMR Electric services between St. Pancras and Corby, which will be run by 110 mph Class 360 trains.

Hitachi’s Three Trains With Batteries

Hitachi have so far announced three battery-electric trains. Two are based on battery packs being developed and built by Hyperdrive Innovation.

Hyperdrive Innovation

Looking at the Hyperdrive Innovation web site, I like what I see.

Hyperdrive Innovation provided the battery packs for JCB’s first electric excavator.

Note that JCB give a five-year warranty on the Hyperdrive batteries.

Hyperdrive have also been involved in the design of battery packs for aircraft push-back tractors.

The battery capacity for one of these is given as 172 kWh and it is able to supply 34 kW.

I was very surprised that Hitachi didn’t go back to Japan for their batteries, but after reading Hyperdrive’s web site about the JCB and Textron applications, there would appear to be good reasons to use Hyperdrive.

- Hyperdrive have experience of large lithium ion batteries.

- Hyperdrive have a design, develop and manufacture model.

- They seem to able to develop solutions quickly and successfully.

- Battery packs for the UK and Europe are made in Sunderland.

- Hyperdrive are co-operating with Nissan, Warwick Manufacturing Group and Newcastle University.

- They appear from the web site to be experts in the field of battery management, which is important in prolonging battery life.

- Hyperdrive have a Taiwanese partner, who manufactures their battery packs for Taiwan and China.

- I have done calculations based on the datasheet for their batteries and Hyperdrive’s energy density is up with the best

I suspect, that Hitachi also like the idea of a local supplier, as it could be helpful in the negotiation of innovative applications. Face-to-face discussions are easier, when you’re only thirty miles apart.

Hitachi Regional Battery Train

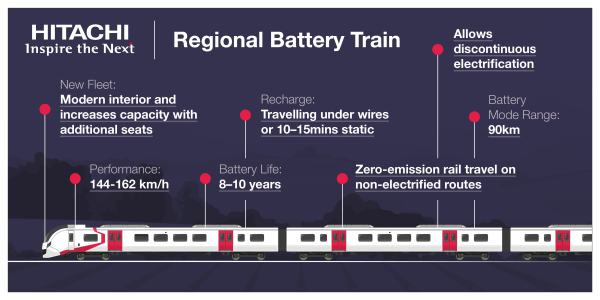

The first train to be announced was the Hitachi Regional Battery Train, which is described in this Hitachi infographic.

Note.

- It is only a 100 mph train.

- The batteries are to be designed and manufactured by Hyperdrive Innovation.

- It has a range of 56 miles on battery power.

- Any of Hitachi’s A Train family like Class 800, 802 or 385 train can be converted to a Regional Battery Train.

No orders have been announced yet.

But it would surely be very suitable for routes like.

- London Paddington And Bedwyn

- London Paddington And Oxford

It would also be very suitable for extensions to electrified suburban routes like.

- London Bridge and Uckfield

- London Waterloo and Salisbury

- Manchester Airport and Windermere.

- Newcastle and Carlisle

It would also be a very sound choice to extend electrified routes in Scotland, which are currently run by Class 385 trains.

Hitachi InterCity Tri-Mode Battery Train

The second train to be announced was the Hitachi InterCity Tri-Mode Battery Train, which is described in this Hitachi infographic.

Note.

- Only one engine is replaced by a battery.

- The batteries are to be designed and manufactured by Hyperdrive Innovation.

- Typically a five-car Class 800 or 802 train has three diesel engines and a nine-car train has five.

- These trains would obviously be capable of 125 mph on electrified main lines and 140 mph on lines fully equipped with digital in-cab ERTMS signalling.

Nothing is said about battery range away from electrification.

Routes currently run from London with a section without electrification at the other end include.

- London Kings Cross And Harrogate – 18.3 miles

- London Kings Cross And Hull – 36 miles

- London Kings Cross And Lincoln – 16.5 miles

- London Paddington And Bedwyn – 13.3 miles

- London Paddington And Oxford – 10.3 miles

In the March 2021 Edition of Modern Railways, LNER are quoted as having aspirations to extend the Lincoln service to Cleethorpes.

- With all energy developments in North Lincolnshire, this is probably a good idea.

- Services could also call at Market Rasen and Grimsby.

- Two trains per day, would probably be a minimum frequency.

But the trains would need to be able to run around 64 miles each way without electrification. Very large batteries and/or charging at Cleethorpes will be needed.

Class 803 Trains For East Coast Trains

East Coast Trains have ordered a fleet of five Class 803 trains.

- These trains appear to be built for speed and fast acceleration.

- They have no diesel engines, which must save weight and servicing costs.

- But they will be fitted with batteries for emergency power to maintain onboard train services in the event of overhead line failure.

- They are planned to enter service in October 2021.

Given that Hyperdrive Innovation are developing traction batteries for the other two Hitachi battery trains, I would not be the least bit surprised if Hyperdrive were designing and building the batteries for the Class 803 trains.

- Hyperdrive batteries are modular, so for a smaller battery you would use less modules.

- If all coaches are wired for a diesel engine, then they can accept any power module like a battery or hydrogen pack, without expensive redesign.

- I suspect too, that the battery packs for the Class 803 trains could be tested on an LNER Class 801 train.

LNER might also decide to replace the diesel engines on their Class 801 trains with an emergency battery pack, if it were more energy efficient and had a lighter weight.

Thoughts On The Design Of The Hyperdrive innovation Battery Packs

Consider.

- Hitachi trains have a sophisticated computer system, which on start-up can determine the configuration of the train or whether it is more than one train running as a longer formation or even being hauled by a locomotive.

- To convert a bi-mode Class 800 train to an all-electric Class 801 the diesel engines are removed. I suspect that the computer is also adjusted, but train formation may well be totally automatic and independent of the driver.

- Hyperdrive Innovation’s battery seem to be based on a modular system, where typical modules have a capacity of 5 kWh, weighs 32 Kg and has a volume of 0.022 cu metres.

- The wet mass of an MTU 16V 1600 R80L diesel engine commonly fitted to AT-300 trains of different types is 6750 Kg or nearly seven tonnes.

- The diesel engine has a physical size of 1.5 x 1.25 x 0.845 metres, which is a volume of 1.6 cubic metres.

- In How Much Power Is Needed To Run A Train At 125 mph?, I calculated that a five-car Class 801 electric train, needed 3.42 kWh per vehicle-mile to maintain 125 mph.

- It is likely, than any design of battery pack, will handle the regenerative braking.

To my mind, the ideal solution would be a plug compatible battery pack, that the train’s computer thought was a diesel engine.

But then I have form in the area of plug-compatible electronics.

At the age of sixteen, for a vacation job, I worked in the Electronics Laboratory at Enfield Rolling Mills.

It was the early sixties and one of their tasks was at the time replacing electronic valve-based automation systems with new transistor-based systems.

The new equipment had to be compatible to that which it replaced, but as some were installed in dozens of places around the works, they had to be able to be plug-compatible, so that they could be quickly changed. Occasionally, the new ones suffered infant-mortality and the old equipment could just be plugged back in, if there wasn’t a spare of the new equipment.

So will Hyperdrive Innovation’s battery-packs have the same characteristics as the diesel engines that they replace?

- Same instantaneous and continuous power output.

- Both would fit the same mountings under the train.

- Same control and electrical power connections.

- Compatibility with the trains control computer.

I think they will as it will give several advantages.

- The changeover between diesel engine and battery pack could be designed as a simple overnight operation.

- Operators can mix-and-match the number of diesel engines and battery-packs to a given route.

- As the lithium-ion cells making up the battery pack improve, battery capacity and performance can be increased.

- If the computer, is well-programmed, it could reduce diesel usage and carbon-emissions.

- Driver conversion from a standard train to one equipped with batteries, would surely be simplified.

As with the diesel engines, all battery packs could be substantially the same across all of Hitachi’s Class 80x trains.

What Size Of Battery Would Be Possible?

If Hyperdrive are producing a battery pack with the same volume as the diesel engine it replaced, I estimate that the battery would have a capacity defined by.

5 * 1.6 / 0.022 = 364 kWh

In an article in the October 2017 Edition of Modern Railways, which is entitled Celling England By The Pound, Ian Walmsley says this in relation to trains running on the Uckfield Branch, which is not very challenging.

A modern EMU needs between 3 and 5 kWh per vehicle mile for this sort of service.

As a figure of 3.42 kWh per vehicle-mile to maintain 125 mph, applies to a Class 801 train, I suspect that a figure of 3 kWh or less could apply to a five-car Class 800 train trundling at around 80-100 mph to Bedwyn, Cleethorpes or Oxford.

- A one-battery five-car train would have a range of 24.3 miles

- A two-battery five-car train would have a range of 48.6 miles

- A three-battery five-car train would have a range of 72.9 miles

Note.

- Reducing the consumption to 2.5 kWh per vehicle-mile would give a range of 87.3 miles.

- Reducing the consumption to 2 kWh per vehicle-mile would give a range of 109.2 miles.

- Hitachi will be working to reduce the electricity consumption of the trains.

- There will also be losses at each station stop, as regenerative braking is not 100 % efficient.

But it does appear to me, that distances of the order of 60-70 miles would be possible on a lot of routes.

Bedwyn, Harrogate, Lincoln and Oxford may be possible without charging before the return trip.

Cleethorpes and Hull would need a battery charge before return.

A Specification For A High Speed Metro Train

I have called the proposed train a High Speed Metro Train, as it would run at up to 140 mph on an existing high speed line and then run a full or limited stopping service to the final destination.

These are a few thoughts.

Electrification

In some cases like London Kings Cross and King’s Lynn, the route is already electrified and batteries would only be needed for the following.

- Handling regenerative braking.

- Emergency power in case of overhead line failure.

- Train movements in depots.

But if the overhead wires on a branch line. are in need of replacement, why not remove them and use battery power? It might be the most affordable and least disruptive option to update the power supply on a route.

The trains would have to be able to run on both types of electrification in the UK.

- 25 KVAC overhead.

- 750 VDC third rail.

This dual-voltage capability would enable the extension of Southeastern Highspeed services.

Operating Speed

The trains must obviously be capable of running at the maximum operating speed on the routes they travel.

- 125 mph on high speed lines, where this speed is possible.

- 140 mph on high speed lines equipped with full digital in-cab ERTMS signalling, where this speed is possible.

The performance on battery power must be matched with the routes.

Hitachi have said, that their Regional Battery trains can run at up to 100 mph, which would probably be sufficient for most secondary routes in the UK and in line with modern diesel and electric multiple units.

Full Digital In-cab ERTMS Signalling

This will be essential and is already fitted to some of Hitachi’s trains.

Regenerative Braking To Batteries

Hitachi’s battery electric trains will probably use regenerative braking to the batteries, as it is much more energy efficient.

It also means that when stopping at a station perhaps as much as 70-80% of the train’s kinetic energy can be captured in the batteries and used to accelerate the train.

In Kinetic Energy Of A Five-Car Class 801 Train, I showed that at 125 mph the energy of a full five-car train is just over 100 kWh, so batteries would not need to be unduly large.

Acceleration

This graph from Eversholt Rail, shows the acceleration and deceleration of a five-car Class 802 electric train.

As batteries are just a different source of electric power, I would think, that with respect to acceleration and deceleration, that the performance of a battery-electric version will be similar.

Although, it will only achieve 160 kph instead of the 200 kph of the electric train.

I estimate from this graph, that a battery-electric train would take around 220 seconds from starting to decelerate for a station to being back at 160 kph. If the train was stopped for around eighty seconds, a station stop would add five minutes to the journey time.

London Kings Cross And Cleethorpes

As an example consider a service between London Kings Cross and Cleethorpes.

- The section without electrification between Newark and Cleethorpes is 64 miles.

- There appear to be ambitions to increase the operating speed to 90 mph.

- Local trains seem to travel at around 45 mph including stops.

- A fast service between London Kings Cross and Cleethorpes would probably stop at Lincoln Central, Market Rasen and Grimsby Town.

- In addition, local services stop at Collingham, Hykeham, Barnetby and Habrough.

- London Kings Cross and Newark takes one hour and twenty minutes.

- London Kings Cross and Cleethorpes takes three hours and fifteen minutes with a change at Doncaster.

I can now calculate a time between Kings Cross and Cleethorpes.

- If a battery-electric train can average 70 mph between Newark and Cleethorpes, it would take 55 minutes.

- Add five minutes for each of the three stops at Lincoln Central, Market Rasen and Grimsby Town

- Add in the eighty minutes between London Kings Cross and Newark and that would be two-and-a-half hours.

That would be very marketing friendly and a very good start.

Note.

- An average speed of 80 mph would save seven minutes.

- An average speed of 90 mph would save twelve minutes.

- I suspect that the current bi-modes would be slower by a few minutes as their acceleration is not as potent of that of an electric train.

I have a feeling London Kings Cross and Cleethorpes via Lincoln Central, Market Rasen and Grimsby Town, could be a very important service for LNER.

Interiors

I can see a new lightweight and more energy efficient interior being developed for these trains.

In addition some of the routes, where they could be used are popular with cyclists and the current Hitachi trains are not the best for bicycles.

Battery Charging

Range On Batteries

I have left this to last, as it depends on so many factors, including the route and the quality of the driving or the Automatic Train Control

Earlier, I estimated that a five-car train with all three diesel engines replaced by batteries, when trundling around Lincolnshire, Oxfordshire or Wiltshire could have range of up to 100 miles.

That sort of distance would be very useful and would include.

- Ely and Norwich

- Newark and Cleethorpes

- Salisbury and Exeter

It might even allow a round trip between the East Coast Main Line and Hull.

The Ultimate Battery Train

This press release from Hitachi is entitled Hitachi And Eversholt Rail To Develop GWR Intercity Battery Hybrid Train – Offering Fuel Savings Of More Than 20%.

This is a paragraph.

The projected improvements in battery technology – particularly in power output and charge – create opportunities to replace incrementally more diesel engines on long distance trains. With the ambition to create a fully electric-battery intercity train – that can travel the full journey between London and Penzance – by the late 2040s, in line with the UK’s 2050 net zero emissions target.

Consider.

- Three batteries would on my calculations give a hundred mile range.

- Would a train with no diesel engines mean that fuel tanks, radiators and other gubbins could be removed and more or large batteries could be added.

- Could smaller batteries be added to the two driving cars?

- By 2030, let alone 2040, battery energy density will have increased.

I suspect that one way or another these trains could have a range on battery power of between 130 and 140 miles.

This would certainly be handy in Scotland for the two routes to the North.

- Haymarket and Aberdeen, which is 130 miles without electrification.

- Stirling and Inverness, which is 111 miles without electrification, if the current wires are extended from Stirling to Perth, which is being considered by the Scottish Government.

The various sections of the London Paddington to Penzance route are as follows.

- Paddington and Newbury – 53 miles – electrified

- Newbury and Taunton – 90 miles – not electrified

- Taunton and Exeter – 31 miles – not electrified

- Exeter and Plymouth – 52 miles – not electrified

- Plymouth and Penzance – 79 miles – not electrified

The total length of the section without electrification between Penzance and Newbury is a distance of 252 miles.

This means that the train will need a battery charge en route.

I think there are three possibilities.

- Trains can take up to seven minutes for a stop at Plymouth. As London and Plymouth trains will need to recharge at Plymouth before returning to London, Plymouth station could be fitted with comprehensive recharge facilities for all trains passing through. Perhaps the ideal solution would be to electrify all lines and platforms at Plymouth.

- Between Taunton and Exeter, the rail line runs alongside the M5 motorway. This would surely be an ideal section to electrify, as it would enable battery electric trains to run between Exeter and both Newbury and Bristol.

- As some trains terminate at Exeter, there would probably need to be charging facilities there.

I believe that the date of the late 2040s is being overly pessimistic.

I suspect that by 2040 we’ll be seeing trains between London and Aberdeen, Inverness and Penzance doing the trips without a drop of diesel.

But Hitachi are making a promise of London and Penzance by zero-carbon trains, by the late-2040s, because they know they can keep it.

And Passengers and the Government won’t mind the trains being early!

Conclusion

This could be a very useful train to add to Hitachi’s product line.

Network Rail’s Big Push

The title of this press release on the Network Rail web site is 11,000 Tonne Tunnel To Be Installed On The Railway In First For UK Engineering.

They have also released this aerial photograph of the tunnel, before it is pushed into place.

Note.

- The tunnel, which is just a curved concrete box is in the middle of the picture.

- To its left is the double-track Peterborough-Lincoln Line.

- Running across the far end of the tunnel are the multiple tracks of the East Coast Main Line.

- Peterborough is a few miles to the left, with the North to the right.

This Google Map shows the same area from directly above.

Note.

- The double-tracks of the Stamford Lines closest to the South-West corner of the map. These link the Peterborough-Birmingham Line to Peterborough.

- Next to them are the triple tracks of the East Coast Main Line.

- The third rail line is the double-track of the Peterborough and Lincoln Line.

- The new tunnel can be seen at the top of the map.

This map from Network Rail, shows the new track layout.

The map shows that the Stamford Line will divide with two tracks (1 and 4) going North to Stamford as now. Two new tracks (2 and 3) will dive-under the East Coast Main Line to join the existing Peterborough and Lincoln Line.

The tracks will run through the tunnel in the pictures, after it has been pushed under the East Coast Main Line.

- This will mean that the many freight trains between Peterborough and Lincoln will not have to cross the East Coast Main Line on the flat.

- This in turn could allow faster running of trains on the East Coast Main Line, that are not stopping at Peterborough.

This second Google Map shows the area to the North of the first map.

Note.

- The East Coast Main Line in the South-West corner of the map.

- The Peterborough and Lincoln Line curving from North-South across the map.

- A bridge would appear to be being constructed to take the A15 road over the new tracks, that will go through the tunnel.

- Another bridge will be constructed to take Lincoln Road over the new tracks.

It is certainly not a small project.

That is emphasised by this third Google Map, which is to the North of the previous map.

This map would appear to show space for more than a pair of tracks.

It looks to me, that space is being left for future rail-related development.

- Could it be for a small freight yard, where trains could wait before proceeding?

- If it were electrified, it could be where freight trains to and from London, switched between electric and diesel power.

- Could it be passing loops, so that freight trains can keep out of the way of faster passenger trains?

- Would it be a place for a possible new station?

If it is to be a full rail freight interchange, I can’t find any mention of it on the Internet.

The Big Push

Summarising, what is said in the press release, I can say.

- Major works to occur over nine days between 16 and 24 January

- It will be pushed at 150cm per hour.

- A reduced level of service will operate.

- It will take several weekends.

I hope it’s being filmed for later broadcasting.

Thoughts On Services

I have a few thoughts on passenger services.

London And Lincoln Via Spalding And Sleaford

Consider.

- Peterborough and Lincoln is 57 miles.

- The route has lots of level crossings.

- Much of the route between Peterborough and Lincoln has an operating speed of 75 mph

- There is a 50 mph limit through Spalding. Is this to cut down noise?

- Trains between Peterborough and Lincoln take a shortest time of one hour and twenty-three minutes, with four stops.

- Peterborough and Lincoln is 57 miles.

- This is an average speed of 41 mph.

I wonder what time a five-car Class 800 train would take to do the journey.

- At an average speed of 50 mph, the train would take 68 minutes and save 15 minutes.

- At an average speed of 60 mph, the train would take 57 minutes and save 26 minutes.

- At an average speed of 70 mph, the train would take 49 minutes and save 18 minutes.

As the fastest London Kings Cross and Peterborough time is 46 minutes, this would mean that with an average speed of 60 mph, a time between London Kings Cross of one hour and forty-three minutes could be possible.

- There could be additional time savings by only stopping at Peterborough, Spalding and Sleaford.

- The Werrington Dive Under looks to be built for speed and could save time.

- If the 50 mph limit through Spalding is down to noise, battery electric trains like a Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train might be able to go through Spalding faster.

- Could some track improvements save time between Peterborough and Lincoln?

As the fastest journeys via Newark to Lincoln take one hour and fifty-six minutes, it looks to me, that LNER might be able to save time by going via Spalding and Sleaford after the Werrington Dive Under opens.

London And Skegness

If there were a fast London train from Sleaford, it will take under an hour and thirty minutes between London Kings Cross and Sleaford.

- Currently, the connecting train between Skegness and Sleaford takes an hour for the forty miles.

- The service is currently run by Class 158 trains.

- With some 100 mph trains on the Skegness and Sleaford service, it might be possible to travel between London and Skegness in two hours and fifteen minutes with a change at Sleaford.

There would appear to be possibilities to improve the service between London and Skegness.

Lincoln And Cambridge

I used to play real tennis at Cambridge with a guy, who was a Cambridge expansionist.

He believed that Cambridge needed more space and that it should strongly rcpand high-tech research, development and manufacturing all the way across the fens to Peterborough and beyond.

I listened to his vision with interest and one thing it needed is a four trains per hour express metro between Cambridge and Peterborough.

- Ely and Peterborough should be electrified for both passenger and freight trains.

- March and Spalding should be reopened.

- Cambridge has the space for new services from the North.

Extending the Lincoln and Peterborough service to Cambridge could be a good start.

Conclusion

The Werrington Dive Under will certainly improve services on the East Coast Main Line.

I also feel, that it could considerably improve rail services between London and South Lincolnshire.

It certainly looks, like Network Rail have designed the Werrington Dive Under to handle more traffic than currently uses the route.

Towns like Boston, Skegness, Sleaford and Spalding aren’t going to complain.

Hitachi Targets Next Year For Testing Of Tri-Mode IET

The title of this post, is the same as that of this article on Rail Magazine.

This is the first two paragraphs.

Testing of a five-car Hitachi Class 802/0 tri-mode unit will begin in 2022, and the train could be in traffic the following year.

It is expected that the train will save more than 20% of fuel on Great Western Railway’s London Paddington-Penzance route.

This is the Hitachi infographic, which gives the train’s specification.

I have a few thoughts and questions.

Will The Batteries Be Charged At Penzance?

Consider.

- It is probably not a good test of customer reaction to the Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train, if it doesn’t work on batteries in stations through Cornwall.

- Every one of the eight stops in Cornwall will need an amount of battery power.

- London trains seem to take at least half-an-hour to turn round at Penzance.

- London trains seem to take around 7-13 minutes for the stop at Plymouth.

So I think, that batteries will probably need to be charged at Penzance and possibly Plymouth, to achieve the required battery running,

There is already sufficient time in the timetable.

A charging facility in Penzance station would be a good test of Hitachi’s method to charge the trains.

Will Hyperdrive Innovation’s Battery Pack Be A Simulated Diesel Engine?

At the age of sixteen, for a vacation job, I worked in the Electronics Laboratory at Enfield Rolling Mills.

It was the early sixties and one of their tasks was at the time replacing electronic valve-based automation systems with new transistor-based systems.

The new equipment had to be compatible to that which it replaced, but as some were installed in dozens of places around the works, they had to be able to be plug-compatible, so that they could be quickly changed. Occasionally, the new ones suffered infant-mortality and the old equipment could just be plugged back in, if there wasn’t a spare of the new equipment.

So will Hyperdrive Innovation’s battery-packs have the same characteristics as the diesel engines that they replace?

- Same instantaneous and continuous power output.

- Both would fit the same mountings under the train.

- Same control and electrical power connections.

- Compatibility with the trains control computer.

I think they will as it will give several advantages.

- The changeover between diesel engine and battery pack could be designed as a simple overnight operation.

- Operators can mix-and-match the number of diesel engines and battery-packs to a given route.

- As the lithium-ion cells making up the battery pack improve, battery capacity and performance can be increased.

- If the computer, is well-programmed, it could reduce diesel usage and carbon-emissions.

- Driver conversion from a standard train to one equipped with batteries, would surely be simplified.

As with the diesel engines, all battery packs could be substantially the same across all of Hitachi’s Class 80x trains.

How Many Trains Can Eventually Be Converted?

Great Western Railway have twenty-two Class 802/0 trains.

- They are five-cars.

- They have three diesel engines in cars 2, 3 and 4.

- They have a capacity of 326 passengers.

- They have an operating speed of 125 mph on electrification.

- They will have an operating speed of 140 mph on electrification with in-cab ERTMS digital signalling.

- They have an operating speed of 110 mph on diesel.

- They can swap between electric and diesel mode at line speed.

Great Western Railway also have these trains that are similar.

- 14 – nine-car Class 802/1 trains

- 36 – five-car Class 800/0 trains

- 21 – nine-car Class 800/3 trains

Note.

- The nine-car trains have five diesel engines in cars 2,3, 5, 7 and 8

- All diesel engines are similar, but those in Class 802 trains are more powerful, than those in Class 800 trains.

This is a total of 93 trains with 349 diesel engines.

In addition, there are these similar trains in service or on order with other operators.

- LNER – 13 – nine-car Class 800/1 trains

- LNER – 10 – five-car Class 800/2 trains

- LNER – 12 – five-car Class 801/1 trains

- LNER – 30 – nine-car Class 801/2 trains

- TransPennine Express – 19 – five-car Class 802/2 trains

- Hull Trains – 5 – five-car Class 802/3 trains

- East Coast Trains – 5 – five-car Class 803 trains

- Avanti West Coast – 13 – five-car Class 805 trains

- Avanti West Coast – 10 – seven-car Class 807 trains

- East Midland Railway – 33 – five-car Class 810 trains

Note.

- Class 801 trains have one diesel engine for emergency power.

- Class 803 trains have no diesel engines, but they do have a battery for emergency power.

- Class 805 trains have an unspecified number of diesel engines. I will assume three.

- Class 807 trains have no batteries or diesel engines.

- Class 810 trains have four diesel engines.

This is a total of 150 trains with 395 diesel engines.

The Rail Magazine finishes with this paragraph.

Hitachi believes that projected improvements in battery technology, particularly in power output and charge, could enable diesel engines to be incrementally replaced on long-distance trains.

Could this mean that most diesel engines on these Hitachi trains are replaced by batteries?

Five-Car Class 800 And Class 802 Trains

These trains are mainly regularly used to serve destinations like Bedwyn, Cheltenham, Chester, Harrogate, Huddersfield, Hull, Lincoln, Oxford and Shrewsbury, which are perhaps up to fifty miles beyond the main line electrification.

- They have three diesel engines, which are used when there is no electrification.

- I can see many other destinations, being added to those reached by the Hitachi trains, that will need similar trains.

I suspect a lot of these destinations can be served by five-car Class 800 and Class 802 trains, where a number of the diesel engines are replaced by batteries.

Each operator would add a number of batteries suitable for their routes.

There are around 150 five-car bi-mode Hitachi trains in various fleets in the UK.

LNER’s Nine-Car Class 800 Trains

These are mainly used on routes between London and the North of Scotland.

In LNER Seeks 10 More Bi-Modes, I suggested that to run a zero-carbon service to Inverness and Aberdeen, LNER might acquire rakes of carriages hauled by zero-carbon hydrogen electric locomotives.

- Hydrogen power would only be used North of the current electrification.

- Scotland is looking to have plenty of hydrogen in a couple of years.

- No electrification would be needed to be erected in the Highlands.

- InterCity 225 trains have shown for forty years, that locomotive-hauled trains can handle Scottish services.

- I also felt that the trains could be based on a classic-compatible design for High Speed Two.

This order could be ideal for Talgo to build in their new factory at Longannet in Fife.

LNER’s nine-car Class 800 trains could be converted to all-electric Class 801 trains and/or moved to another operator.

There is also the possibility to fit these trains with a number of battery packs to replace some of their five engines.

If the planned twenty percent fuel savings can be obtained, that would be a major improvement on these long routes.

LNER’s Class 801 Trains

These trains are are all-electric, but they do have a diesel engine for emergencies.

Will this be replaced by a battery pack to do the same job?

- Battery packs are probably cheaper to service.

- Battery packs don’t need diesel fuel.

- Battery packs can handle regenerative braking and may save electricity.

The installation surely wouldn’t need too much test running, as a lot of testing will have been done in Class 800 and Class 802 trains.

East Coast Trains’ Class 803 Trains

These trains have a slightly different powertrain to the Class 801 trains. Wikipedia says this about the powertrain.

Unlike the Class 801, another non-bi-mode AT300 variant which despite being designed only for electrified routes carries a diesel engine per unit for emergency use, the new units will not be fitted with any, and so would not be able to propel themselves in the event of a power failure. They will however be fitted with batteries to enable the train’s on-board services to be maintained, in case the primary electrical supplies would face a failure.

The trains are in the process of being built, so I suspect batteries can be easily fitted.

Could it be, that all five-car trains are identical body-shells, already wired to be able to fit any possible form of power? Hitachi have been talking about fitting batteries to their trains since at least April 2019, when I wrote, Hitachi Plans To Run ScotRail Class 385 EMUs Beyond The Wires.

- I suspect that Hitachi will use a similar Hyperdrive Innovation design of battery in these trains, as they are proposing for the Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train.

- If all trains fitted with diesel engines, use similar MTU units, would it not be sensible to only use one design of battery pack?

- I suspect, that as the battery on a Class 803 train, will be mainly for emergency use, I wouldn’t be surprised to see that these trains could be the first to run in the UK, with a battery.

- The trains would also be simpler, as they are only battery-electric and not tri-mode. This would make the software easier to develop and test.

If all trains used the same battery pack design, then all features of the pack, would be available to all trains to which it was fitted.

Avanti West Coast’s Class 805 Trains

In Hitachi Trains For Avanti, which was based on an article with the same time in the January 2020 Edition of Modern Railways, I gave this quote from the magazine article.

Hitachi told Modern Railways it was unable to confirm the rating of the diesel engines on the bi-modes, but said these would be replaceable by batteries in future if specified.

Note.

- Hitachi use diesel engines with different ratings in Class 800 and Class 802 trains, so can probably choose something suitable.

- The Class 805 trains are scheduled to be in service by 2022.

- As they are five-cars like some Class 800 and Class 802 trains will they have the same basic structure and a powertrain with three diesel engines in cars 2, 3 and 4?

I think shares a basic structure and powertrain will be very likely, as there isn’t enough time to develop a new train.

I can see that as Hitachi and Great Western Railway learn more about the performance of the battery-equipped Class 802 trains on the London and Penzance route, that batteries could be added to Avanti West Coast’s Class 805 trains. After all London Euston and North Wales and London Paddington and Cornwall are routes with similar characteristics.

- Both routes have a high speed electrified section out of London.

- They have a long section without electrification.

- Operating speeds on diesel are both less than 100 mph, with sections where they could be as low as 75 mph.

- The Cornish route has fifteen stops and the Welsh route has seven, so using batteries in stations will be a welcome innovation for passengers and those living near the railway.

As the order for the Avanti West Coast trains was placed, whilst Hitachi were probably designing their battery electric upgrade to the Class 800 and Class 802 trains, I can see batteries in the Class 805 trains becoming an early reality.

In Hitachi Trains For Avanti, I also said this.

Does the improvement in powertrain efficiency with smaller engines running the train at slower speeds help to explain this statement from the Modern Railways article?

Significant emissions reduction are promised from the elimination of diesel operation on electrified sections as currently seen with the Voyagers, with an expected reduction in CO2 emissions across the franchise of around two-thirds.

That is a large reduction, which is why I feel, that efficiency and batteries must play a part.

Note.

- The extract says that they are expected savings not an objective for some years in the future.

- I have not done any calculations on how it might be achieved, as I have no data on things like engine size and expected battery capacity.

- Hitachi are aiming for 20 % fuel and carbon savings on London Paddington and Cornwall services.

- Avanti West Coast will probably only be running Class 805 trains to Chester, Shrewsbury and North Wales.

- The maximum speed on any of the routes without electrification is only 90 mph. Will less powerful engines be used to cut carbon emissions?

As Chester is 21 miles, Gobowen is 46 miles, Shrewsbury is 29.6 miles and Wrexham General is 33 miles from electrification, could these trains have been designed with two diesel engines and a battery pack, so that they can reach their destinations using a lot less diesel.

I may be wrong, but it looks to me, that to achieve the expected reduction in CO2 emissions, the trains will need some radical improvements over those currently in service.

Avanti West Coast’s Class 807 Trains

In the January 2020 Edition of Modern Railways, is an article, which is entitled Hitachi Trains For Avanti.

This is said about the ten all-electric Class 807 trains for Birmingham, Blackpool and Liverpool services.

The electric trains will be fully reliant on the overhead wire, with no diesel auxiliary engines or batteries.

It may go against Hitachi’s original design philosophy, but not carrying excess weight around, must improve train performance, because of better acceleration.

I believe that these trains have been designed to be able to go between London Euston and Liverpool Lime Street stations in under two hours.

I show how in Will Avanti West Coast’s New Trains Be Able To Achieve London Euston and Liverpool Lime Street In Two Hours?

Consider.

- Current London Euston and Liverpool Lime Street timings are two hours and thirteen or fourteen minutes.

- I believe that the Class 807 trains could perhaps be five minutes under two hours, with a frequency of two trains per hour (tph)

- I have calculated in the linked post, that only nine trains would be needed.

- The service could have dedicated platforms at London Euston and Liverpool Lime Street.

- For comparison, High Speed Two is promising one hour and thirty-four minutes.

This service would be a Marketing Manager’s dream.

I can certainly see why they won’t need any diesel engines or battery packs.

East Midland Railway’s Class 810 Trains

The Class 810 trains are described like this in their Wikipedia entry.

The Class 810 is an evolution of the Class 802s with a revised nose profile and facelifted end headlight clusters, giving the units a slightly different appearance. Additionally, there will be four diesel engines per five-carriage train (versus three on the 800s and 802s), and the carriages will be 2 metres (6.6 ft) shorter.

In addition, the following information has been published about the trains.

- The trains are expected to be capable of 125 mph on diesel.

- Is this speed, the reason for the fourth engine?

- It is planned that the trains will enter service in 2023.

I also suspect, that like the Class 800, Class 802 and Class 805 trains, that diesel engines will be able to be replaced with battery packs.

Significant Dates And A Possible Updating Route For Hitachi Class 80x Trains

I can put together a timeline of when trains are operational.

- 2021 – Class 803 trains enter service.

- 2022 – Testing of prototype Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train

- 2022 – Class 805 trains enter service.

- 2022 – Class 807 trains enter service.

- 2023 – First production Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train enters service.

- 2023 – Class 810 trains enter service.

Note.

- It would appear to me, that Hitachi are just turning out trains in a well-ordered stream from Newton Aycliffe.

- As testing of the prototype Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train proceeds, Hitachi and the operators will learn how, if batteries can replace some or even all of the diesel engines, the trains will have an improved performance.

- From about 2023, Hitachi will be able to design tri-mode trains to fit a customer’s requirements.

- Could the powertrain specification of the Class 810 trains change, in view of what is shown by the testing of the prototype Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train?

- In parallel, Hyperdrive Innovation will be building the battery packs needed for the conversion.

Batteries could be fitted to the trains in three ways,

- They could be incorporated into new trains on the production line.

- Batteries could be fitted in the depots, during a major service.

- Trains could be returned to Newton Aycliffe for battery fitment.

Over a period of years as many trains as needed could be fitted with batteries.

Conclusion

I believe there is a plan in there somewhere, which will convert many of Hitachi’s fleets of trains into tri-mode trains with increased performance, greater efficiency and less pollution and carbon emissions.

Shooter Urges Caution On Hydrogen Hubris

The title of this post is the same as that of an article in the January 2021 Edition of Modern Railways.

This is the first paragraph.

Vivarail Chairman Adrian Shooter has urges caution about the widespread enthusiasm for hydrogen technology. In his keynote speech to the Golden Spanner Awards on 27 November, Mr. Shooter said the process to create ‘green hydrogen’ by electrolysis is ‘a wasteful use of electricity’ and was skeptical about using electricity to create hydrogen to then use a fuel cell to power a train, rather than charging batteries to power a train. ‘What you will discover is that a hydrogen train uses 3.5 times as much electricity because of inefficiencies in the electrolysis process and also in the fuel cells’ said Mr. Shooter. He also noted the energy density of hydrogen at 350 bar is only one-tenth of a similar quantity of diesel fuel, severely limiting the range of a hydrogen-powered train between refuelling.

Mr. Shooter then made the following points.

- The complexity of delivering hydrogen to the railway depots.

- The shorter range available from the amount of hydrogen that can be stored on a train compared to the range of a diesel train.

- He points out limitations with the design of the Alstom Breeze train.

This is the last paragraph.

Whilst this may have seemed like a challenge designed purely to promote the battery alternatives that Vivarail is developing, and which he believes to be more efficient, Mr. Shooter explained: ‘I think that hydrogen fuel cell trains could work in this country, but people just need to remember that there are downsides. I’m sure we’ll see some, and in fact we should because competition improves the breed.’

i think Mr. Shooter may have made several good points.

These are my thoughts.

Creating Green Hydrogen

I haven’t done an analysis of the costs of creating green hydrogen from electrolysis, but I have a feeling, that electrolysis won’t be the only way to create large amounts of carbon-free hydrogen, in a few years.

These methods are currently available or under development or construction.

- The hydrogen tram-buses in Pau have a personal electrolyser, that provides hydrogen at 350 bar.

- London’s hydrogen buses will be provided with hydrogen from an electrolyser at Herne Bay by truck. Will the trucks be hydrogen-powered?

Some industrial processes like the Castner-Kellner process create hydrogen as a by-product.

In Shell Process To Make Blue Hydrogen Production Affordable, I describe the Shell Blue Hydrogen Process, which appears to be a way of making massive amounts of carbon-free hydrogen for processes like steel-making and cement production. Surely some could be piped or transported by truck to the rail depot.

In ITM Power and Ørsted: Wind Turbine Electrolyser Integration, I describe how ITM Power and Ørsted plan to create the hydrogen off shore and bring it by pipeline to the shore.

Note.

- The last two methods could offer savings in the cost of production of carbon-free hydrogen.

- Surely, the delivery trucks if used, must be hydrogen-powered.

- The Shell Blue Hydrogen Process uses natural gas as a feedstock and converts it to hydrogen using a newly-developed catalyst. The carbon-dioxide is captured and used or stored.

- If the local gas network has been converted to hydrogen, the hydrogen can be delivered to the depot or filling station through that gas network.

I very much feel that affordable hydrogen can be supplied to bus, train, tram or transport depot. For remote or difficult locations. personal electrolysers, powered by renewable electricity, can be used, as at Pau.

Hydrogen Storage On Trains

Liquid hydrogen could be the answer and Airbus are developing methods of storing large quantities on aircraft.

In What Size Of Hydrogen Tank Will Be Needed On A ZEROe Turbofan?, I calculated how much liquid hydrogen would be needed for this ZEROe Turbofan.

I calculate that to carry the equivalent amount of fuel to an Airbus A320neo would need a liquid hydrogen tank with a near 100 cubic metre capacity. This sized tank would fit in the rear fuselage.

I feel that in a few years, a hydrogen train will be able to carry enough liquid hydrogen in a fuel tank, but the fuel tank will be large.

In The Mathematics Of A Hydrogen-Powered Freight Locomotive, I calculated how much liquid hydrogen would be needed to provide the same amount of energy as that carried in a full diesel tank on a Class 68 locomotive.

The locomotive would need 19,147 litres or 19.15 cubic metres of liquid hydrogen, which could be contained in a cylindrical tank with a diameter of 2 metres and a length of 6 metres.

Hydrogen Locomotives Or Multiple Units?

We have only seen first generation hydrogen trains so far.

This picture shows the Alstom Coradia iLint, which is a conversion of a Coradia Lint.

It is a so-so train and works reasonably well, but the design means there is a lot of transmission noise.

This is a visualisation of an Alstom Breeze or Class 600 train.

Note that the front half of the first car of the train, is taken up with a large hydrogen tank. It will be the same at the other end of the train.

As Mr. Shooter said, Alstom are converting a three-car train into a two-car train. Not all conversions live up to the hype of their proposers.

I would hope that the next generation of a hydrogen train designed from scratch, will be a better design.

I haven’t done any calculations, but I wonder if a lighter weight vehicle may be better.

Hydrogen Locomotives

I do wonder, if hydrogen locomotives are a better bet and easier to design!

- There is a great need all over the world for zero-carbon locomotives to haul freight trains.

- Powerful small gas-turbine engines, that can run on liquid hydrogen are becoming available.

- Rolls-Royce have developed a 2.5 MW gas-turbine generator, that is the size of a beer-keg.

In The Mathematics Of A Hydrogen-Powered Freight Locomotive, I wondered if the Rolls-Royce generator could power a locomotive, the size of a Class 68 locomotive.

This was my conclusion.

I feel that there are several routes to a hydrogen-powered railway locomotive and all the components could be fitted into the body of a diesel locomotive the size of a Class 68 locomotive.

Consider.

- Decarbonising railway locomotives and ships could be a large market.

- It offers the opportunities of substantial carbon reductions.

- The small size of the Rolls-Royce 2.5 MW generator must offer advantages.

- Some current diesel-electric locomotives might be convertible to hydrogen power.

I very much feel that companies like Rolls-Royce and Cummins (and Caterpillar!), will move in and attempt to claim this lucrative worldwide market.

In the UK, it might be possible to convert some existing locomotives to zero-carbon, using either liquid hydrogen, biodiesel or aviation biofuel.

Perhaps, hydrogen locomotives could replace Chiltern Railways eight Class 68 locomotives.

- A refuelling strategy would need to be developed.

- Emissions and noise, would be reduced in Marylebone and Birmingham Moor Street stations.

- The rakes of carriages would not need any modifications to use existing stations.

It could be a way to decarbonise Chiltern Railways without full electrification.

It looks to me that a hydrogen-powered locomotive has several advantages over a hydrogen-powered multiple unit.

- It can carry more fuel.

- It can be as powerful as required.

- Locomotives could work in pairs for more power.

- It is probably easier to accommodate the hydrogen tank.

- Passenger capacity can be increased, if required by adding more coaches.

It should also be noted that both hydrogen locomotives and multiple units can build heavily on technology being developed for zero-carbon aviation.

The Upward Curve Of Battery Power

Sparking A Revolution is the title an article in Issue 898 of Rail Magazine, which is mainly an interview with Andrew Barr of Hitachi Rail.

The article contains a box, called Costs And Power, where this is said.

The costs of batteries are expected to halve in the next years, before dropping further again by 2030.

Hitachi cites research by Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) which expects costs to fall from £135/kWh at the pack level today to £67/kWh in 2030 and £47/kWh in 3030.

United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) are predicting that battery energy density will double in the next 15 years, from 700 Wh/l to 1400 Wh/l in 2-35, while power density (fast charging) is likely to increase four times in the same period from 3 kW/kg to 12 kW/kg in 2035.

These are impressive improvements that can only increase the performance and reduce the cost of batteries in all applications.

Hitachi’s Regional Battery Train

This infographic gives the specification of Hitachi Regional Battery Train, which they are creating in partnership with Hyperdrive Innovation.

Note that Hitachi are promising a battery life of 8-10 years.

Financing Batteries

This paragraph is from this page on BuyaCar, which is entitled Electric Car Battery Leasing: Should I Lease Or Buy The Batteries?

When you finance or buy a petrol or diesel car it’s pretty simple; the car will be fitted with an engine. However, with some electric cars you have the choice to finance or buy the whole car, or to pay for the car and lease the batteries separately.

I suspect that battery train manufacturers, will offer similar finance models for their products.

This paragraph is from this page on the Hyperdrive Innovation web site.

With a standardised design, our modular product range provides a flexible and scalable battery energy storage solution. Combining a high-performance lithium-ion NMC battery pack with a built in Battery Management System (BMS) our intelligent systems are designed for rapid deployment and volume manufacture, supplying you with class leading energy density and performance.

I can envisage that as a battery train ages, every few years or so, the batteries will get bigger electrically, but still be the same physical size, due to the improvements in battery technology, design and manufacture.

I have been involved in the finance industry both as a part-owner of a small finance company and as a modeller of the dynamics of their lending. It looks to me, that train batteries could be a very suitable asset for financing by a fund. But given the success of energy storage funds like Gore Street and Gresham House, this is not surprising.

I can envisage that battery electric trains will be very operator friendly, as they are likely to get better with age and they will be very finance-friendly.

Charging Battery Trains

I must say something about the charging of battery trains.

Battery trains will need to be charged and various methods are emerging.

Using Existing Electrification

This will probably be one of the most common methods used, as many battery electric services will be run on partly on electrified routes.

Take a typical route for a battery electric train like London Paddington and Oxford.

- The route is electrified between London Paddington and Didcot Junction.

- There is no electrification on the 10.4 miles of track between Didcot Junction and Oxford.

If a full battery on the train has sufficient charge to take the train from Didcot Junction to Oxford and back, charging on the main line between London Paddington and Didcot Junction, will be all that will be needed to run the service.

I would expect that in the UK, we’ll be seeing battery trains using both 25 KVAC overhead and 750 VDC third rail electrification.

Short Lengths Of New Strategic Electrification

I think that Great Western Railway would like to run either of Hitachi’s two proposed battery electric trains to Swansea.

As there is 45.7 miles pf track without .electrification, some form of charging in Swansea station, will probably be necessary.

The easiest way would probably be to electrify Swansea station and perhaps for a short distance to the North.

This Google Map shows Swansea station and the railway leading North.

Note.

- There is a Hitachi Rail Depot at the Northern edge of the map.

- Swansea station is in South-West corner of the map.

- Swansea station has four platforms.

Swansea station would probably make an excellent battery train hub, as trains typically spend enough time in the station to fully charge the batteries before continuing.

There are other tracks and stations of the UK, that I would electrify to enable the running of battery electric trains.

- Leeds and York, which would enable carbon-free London and Edinburgh services via Leeds and help TransPennine services. This is partially underway.

- Leicester and East Midlands Parkway and Clay Cross North Junction and Sheffield – These two sections would enable EMR InterCity services to go battery electric.

- Sheffield and Leeds via Meadowhall, Barnsley Dearne Valley and the Wakefield Line, which would enable four trains per hour (tph) between Sheffield and Leeds and an extension of EMR InterCity services to Leeds.

- Hull and Brough, would enable battery electric services to Hull and Beverley.

- Scarborough and Seamer, would enable electric services services to Scarborough and between Hull and Scarborough.

- Middlesbrough and Redcar, would enable electric services services to Teesside.

- Crewe and Chester and around Llandudno Junction station – These two sections would enable Avanti West Coast service to Holyhead to go battery electric.

- Shrewsbury station – This could become a battery train hub, as I talked about for Swansea.

- Taunton and Exeter and around Penzance, Plymouth and Westbury stations – These three sections would enable Great Western Railway to cut a substantial amount of carbon emissions.

- Exeter, Yeovil Junction and Salisbury stations. – Electrifying these three stations would enable South Western Railway to run between London and Exeter using Hitachi Regional Battery Trains, as I wrote in Bi-Modes Offered To Solve Waterloo-Exeter Constraints.

We will also need fast chargers for intermediate stations, so that a train can charge the batteries on a long route.

I know of two fast chargers under development.

- Opbrid at Furrer + Frey

- Vivarail’s Fast Charge, which I wrote about in Vivarail’s Plans For Zero-Emission Trains.

I believe it should be possible to battery-electrify a route by doing the following.

- Add short lengths of electrification and fast charging systems as required.

- Improve the track, so that trains can use their full performance.

- Add ERTMS signalling.

- Add some suitable trains.

Note.

- I feel ERTMS signalling with a degree of automatic train control could be used with automatic charging systems, to make station stops more efficient.

- In my view, there is no point in installing better modern trains, unless the track is up to their performance.

Possible Destinations For An Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train

Currently, the following routes are run or are planned to be run by Hitachi’s Class 800, 802, 805 and 810 trains, where most of the route is electrified and sections do not have any electrification.

- Avanti West Coast – Euston and Chester – 21 miles

- Avanti West Coast – Euston and Shewsbury – 29.6 miles

- Avanti West Coast – Euston and Wrexham General – 33 miles

- Grand Central – Kings Cross and Sunderland – 47 miles

- GWR – Paddington and Bedwyn – 13.3 miles

- GWR – Paddington and Bristol Temple Meads- 24.5 miles

- GWR – Paddington and Cheltenham – 43.3 miles

- GWR – Paddington and Great Malvern – 76 miles

- GWR – Paddington and Oxford – 10.4 miles

- GWR – Paddington and Penzance – 252 miles

- GWR – Paddington and Swansea – 45.7 miles

- Hull Trains – Kings Cross and Hull – 36 miles

- LNER – Kings Cross and Harrogate – 18.5 miles

- LNER – Kings Cross and Huddersfield – 17 miles

- LNER – Kings Cross and Hull – 36 miles

- LNER – Kings Cross and Lincoln – 16.5 miles

- LNER – Kings Cross and Middlesbrough – 21 miles

- LNER – Kings Cross and Sunderland – 47 miles

Note.

- The distance is the length of line on the route without electrification.

- Five of these routes are under twenty miles

- Many of these routes have very few stops on the section without electrification.

I suspect that Avanti West Coast, Grand Central, GWR and LNER have plans for other destinations.

A Battery Electric Train With A Range of 56 Miles

Hitachi’s Regional Battery Train is deescribed in this infographic.

The battery range is given as 90 kilometres or 56 miles.

This battery range would mean that of the fifteen destinations I proposed, the following could could be achieved on a full battery.

- Chester

- Shewsbury

- Wrexham General

- Bedwyn

- Bristol Temple Meads

- Cheltenham

- Oxford

- Swansea

- Hull

- Harrogate

- Huddersfield

- Lincoln

- Middlesbrough

Of these a return trip could probably be achieved without charging to Chester, Shrewsbury, Bedwyn, Bristol Temple Meads, Oxford, Harrogate, Huddersfield, Lincoln and Middlesbrough.

- 86.7 % of destinations could be reached, if the train started with a full battery

- 60 % of destinations could be reached on an out and back basis, without charging at the destination.

Only just over a quarter of the routes would need, the trains to be charged at the destination.

Conclusion

It looks to me, that Hitachi have done some analysis to determine the best battery size. But that is obviously to be expected.

Charging The Batteries On An Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train

There are several ways the batteries on an Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train could be charged.

- On an electrified main line like the Great Western or East Coast Main Lines, the electrification can be used in normal electrified running.

- A short length of electrification at the terminal or through stations can be used.

- The diesel engines could be used, at stations, where this is acceptable.

Alternatively, a custom design of charger can be used like Vivarail’s Fast Charge system.

In Vivarail’s Plans For Zero-Emission Trains, I said this.

Vivarail Now Has Permission To Charge Any Train

Mr. Shooter said this about Vivarail’s Fast Charge system.

The system has now been given preliminary approval to be installed as the UK’s standard charging system for any make of train.

I may have got the word’s slightly wrong, but I believe the overall message is correct.

In the November 2020 Edition of Modern Railways, there is a transcript of what Mr. Shooter said.

‘Network Rail has granted interim approval for the fast charge system and wants it to be the UK’s standard battery charging system’ says Mr. Shooter. ‘We believe it could have worldwide implications.’

I hope Mr. Shooter knows some affordable lawyers, as in my experience, those working in IPR are not cheap.

I think it’s very likely, that Vivarail’s Fast Charge system could be installed at terminals to charge Hitachi’s Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Trains.

-

- The Fast Charge systems can be powered by renewable energy.

- The trains would need to be fitted with third rail shoes modified to accept the high currents involved.

- They can also be installed at intermediate stations on unelectrified lines.

Vivarail is likely to install a Fast Charge system at a UK station in the next few months.

These are my thoughts about charging trains at various stations.

Penzance station

This Google Map shows Penzance station.

Penzance would be an ideal station to fully charge the trains, before they ran East.

- The station has four long platforms.

- There appears to be plenty of space just to the East of the station.

- Penzance TMD is nearby.

This picture shows Platform 4, which is on the seaward side of the station. The train in the platform is one of GWR’s Castles.

It is partly outside the main station, so might be very suitable to charge a train.

If trials were being performed to Penzance, it appears that the station would be a superb choice to charge trains.

My only worry, is would the location have enough power to charge the trains?

Plymouth Station

This Google Map shows Plymouth station.

It is another spacious station with six platforms.

Chargers could be installed as needed for both expresses and local trains.

A Zero-Carbon Devon and Cornwall

If the battery trains perform as expected, I can see the Devon and Cornwall area becoming a low if not zero carbon railway by the end of this decade.

- The Castles would be retired.

- They would be replaced by battery electric trains.

- Charging would be available on all platforms at Penzance, Plymouth and possible some other intermediate stations and those on some branch lines.

It certainly wouldn’t hurt tourism.

Thoughts On Batteries In East Midland Railway’s Class 810 Trains

Since Hitachi announced the Regional Battery Train in July 2020, which I wrote about in Hyperdrive Innovation And Hitachi Rail To Develop Battery Tech For Trains, I suspect things have moved on.

This is Hitachi’s infographic for the Regional Battery Train.

Note.

- The train has a range of 90 km/56 miles on battery power.

- Speed is given at between 144 kph/90 mph and 162 kph/100 mph

- The performance using electrification is not given, but it is probably the same as similar trains, such as Class 801 or Class 385 trains.

- Hitachi has identified its fleets of 275 trains as potential early recipients.

It is also not stated how many of the three diesel engines in a Class 800 or Class 802 trains will be replaced by batteries.

I suspect if the batteries can be easily changed for diesel engines, operators will be able to swap diesel engines and battery packs according to the routes.

Batteries In Class 803 Trains

I first wrote about the Class 803 trains for East Coast Trains in Trains Ordered For 2021 Launch Of ‘High-Quality, Low Fare’ London – Edinburgh Service, which I posted in March 2019.

This sentence from Wikipedia, describes a big difference between Class 803 and Class 801 trains.

Unlike the Class 801, another non-bi-mode AT300 variant which despite being designed only for electrified routes carries a diesel engine per unit for emergency use, the new units will not be fitted with any, and so would not be able to propel themselves in the event of a power failure. They will however be fitted with batteries to enable the train’s on-board services to be maintained, in case the primary electrical supplies would face a failure.

Nothing is said about how the battery is charged. It will probably be charged from the overhead power, when it is working.

The Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train

Hitachi announced the Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train in this press release in December 2020.

This is Hitachi’s infographic for the Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train.

Note.

- The train is battery-powered in stations and whilst accelerating away.