Stonehenge Tunnel Campaigners Win Court Battle

The title of this post, is the same as that of this article on the BBC.

This is the first part of the BBC article.

Campaigners have won a court battle to prevent the “scandalous” construction of a road tunnel near Stonehenge.

The £1.7bn Highways England project aimed to reduce A303 congestion but campaigners said it would detrimentally affect the world heritage site.

The government approved plans in 2020 for a two-mile (3.2km) tunnel to be created near the Wiltshire monument.

Mr Justice Holgate’s ruling means the order granted by transport secretary Grant Shapps has been quashed.

I obtained my driving licence in 1964 and since then the A303 past Stonehenge has been a worsening bottleneck.

I suspect that unreleased papers from successive governments since the 1960s would show that most Ministers of Transport hoped the problem of Stonehenge would be solved by the next Government of a different colour, which would hopefully lose them the next election.

If you read the whole of the BBC article you’ll see a large map from Highways England.

Note.

- The proposed tunnel is shown as a dotted red line to the South of Stonehenge, more or less following the line of the current A303.

- The Amesbury by-pass already exists in the East.

- A new Winterbourne Stoke by-pass will be built in the West.

Some feel that a longer tunnel might be the solution.

But it would probably need to start to the West of Winterbourne Stoke and be at least three times longer than the proposed tunnel.

So this short stretch of road would then probably cost around £5billion.

Can We Reduce The Traffic On This Road?

There are several ways that traffic might be reduced.

Universal Road Pricing

Every vehicle would be fitted with a meter, which charged drivers depending on the following.

- The type of vehicle.

- The congestion on the road.

- The speed, at which the vehicle is travelling.

It might work, but any government introducing universal road pricing would lose the next General Election by a landslide.

Tolls On Parts Of The A303

Again it might work and push drivers to find other routes.

Improve Other Routes Like The M4

As capacity is increased on other routes, drivers could be lured away from the busy section of the A303 around Stonehenge.

Improve Rail Services Between Paddington And West Of Exeter

I know because of friends, who regularly go to Devon and \Cornwall for both weekends and longer holidays, that many people go to the far-South West by car and most will use the A303 route to and from London.

These services are run by Great Western Railway and the destinations in the South West are not as comprehensive as they could be.

- GWR’s Class 802 trains can split and join efficiently, which could mean they could serve more destinations with the same number of trains.

- GWR seem to be in favour of developing more direct services between London and Bodmin, Okehampton and other places.

- GWR are adding stations to their network in the South-West.

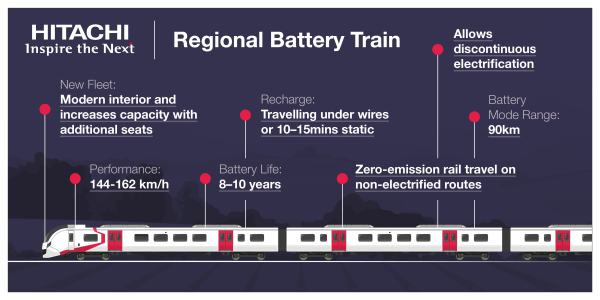

But most importantly, GWR, Hitachi and the Eversholt Rail Group are developing the Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train, which will lower carbon-emissions on the route. This Hitachi infographic describes the train.

These trains could attract numbers of car drivers to use the train, rather than drive.

Improve The Night Riviera Between Paddington And Penzance

Most other sleeper trains in Europe have renewed their fleet.

An improvement in the rolling stock could encourage more people to travel this way.

Improve Rail Services Between Waterloo And Exeter

The rail line between Waterloo and Exeter via Basingstoke and Salisbury runs within a dozen miles of Stonehenge.

- The rolling stock is thirty-year-old British Rail diesel trains.

- It is not electrified to the West of Basingstoke.

- There are portions of single-track railway.

The Waterloo and Exeter line could be improved.

- Remove some sections of single track.

- Upgrade the operating speed to up to 100 mph in places.

- Use a version of the latest Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train

- Add some new stations.

I believe the quality, frequency and journey times of the service could all be improved.

Would this second fast route from the South-West encourage more to take the train?

Stonehenge And Wilton Junction Station

Stonehenge may be the problem, but it can also be part of the solution.

In The Proposal For Stonehenge And Wilton Junction Station, I write about an innovative proposal, that uses a car park at a new station to create a Park-And-Ride for both Stonehenge and Salisbury.

This could bring more visitors to Stonehenge without their cars.

Conclusion

None of these proposals will take vast amounts of pressure from the A303. But every little helps.

Some like the decarbonisation of rail services will have to be done anyway.

Thoughts On Train Times Between London Paddington And Cardiff Central

I went to Cardiff from Paddington on Tuesday.

These were the journey details.

- Distance – Paddington and Cardiff – 145.1 miles

- Time – Paddington and Cardiff – 110 minutes – 79.1 mph

- Time – Cardiff and Paddington- 114 minutes – 76.4 mph

There were four stops. Each seemed to take between two and three minutes.

I do feel though, that the trains are still running to a timetable, that could be run by an InterCity 125.

I watched the Speedview app on my phone for a lot of both journeys.

- There was quite an amount of 125 mph running on the route.

- Some stretches of the route seemed to be run at a line speed of around 90 mph.

- The Severn Tunnel appears to have a 90 mph speed.

- Coming back to London the train ran at 125 mph until the Wharncliffe Viaduct.

These are my thoughts.

Under Two Hour Service

The current service is under two hours, which is probably a good start.

Improving The Current Service

It does strike me that the current timetable doesn’t take full advantage of the performance of the new Hitachi Class 80x trains.

- Could a minute be saved at each of the four stops?

- Could more 125 mph running be introduced?

- Could the trains go faster through the Severn Tunnel?

- If two trains per hour (tph) were to be restored, would that allow a more efficient stopping pattern?

- The route has at least four tracks between Paddington and Didcot Parkway and the Severn Tunnel and Cardiff.

I would reckon that times of between one hour and forty minutes and one hour and forty-five minutes are possible.

These times correspond to average speeds of between 87 and 83 mph.

Application of In-Cab Digital Signalling

Currently, a typical train leaving Paddington completes the 45.7 miles between Hanwell and Didcot Parkway with a stop at Reading in 28 minutes, which is an average speed of 97.9 mph.

This busy section of the route is surely an obvious one for In-cab digital signalling., which would allow speeds of up to 140 mph.

- Services join and leave the route on branches to Bedwyn, Heathrow, Oxford and Taunton.

- The Heathrow services are run by 110 mph Class 387 trains.

- There are slow lines for local services and freight trains.

If an average speed of 125 mph could be attained between Hanwell and Didcot Parkway, this would save six minutes on the time.

Would any extra savings be possible on other sections of the route, by using in-cab digital signalling?

I suspect on the busy section between Bristol Parkway and Cardiff Central stations several minutes could be saved.

Would A Ninety Minute Time Between Paddington And Cardiff Be Possible?

To handle the 145.1 miles between Paddington and Cardiff Central would require an average speed including four stops of 96.7 mph.

This average speed is in line with the current time between Hanwell and Didcot Parkway with a stop at Reading, so I suspect that with improvements to the timetable, that a ninety minute service between Paddington and Cardiff Central is possible.

It may or may not need in-cab digital signalling.

My Control Engineer’s nose says that this signalling upgrade will be needed.

Would A Sixty Minute Time Between Paddington And Cardiff Be Possible?

A journey time of an hour between Paddington and Cardiff Central would surely be the dream of all politicians the Great Western Railway and many of those involved with trains.

To handle the 145.1 miles between Paddington and Cardiff Central would require an average speed including four stops of 145.1 mph.

It would probably be difficult to maintain a speed a few mph above the trains current maximum speed for an hour.

- How many minutes would be saved with perhaps a single intermediate stop at Bristol Parkway station?

- Perhaps the Cardiff service could be two tph in ninety minutes and one tph in sixty minutes.

- Full in-cab digital signalling would certainly be needed.

- Faster trains with a maximum speed of up to 155-160 mph would certainly be needed.

- There may be a need for some extra tracks in some places on the route.

A journey time of an hour will be a few years coming, but I feel it is an achievable objective.

The Extended Route To Swansea

Cardiff Central and Swansea is a distance of 45.7 miles

A typical service takes 55 minutes with three stops, at an average speed of 49.8 mph.

This would be an ideal route for a Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train, which is described in this Hitachi infographic.

It would probably be needed to be charged at Swansea station, to both enable return to Cardiff Central or extend the service to the West of Swansea.

Conclusion

Big improvements in journey times between Paddington and Cardiff Central are possible.

Vivarail At COP26

This press release from Network Rail is entitled Network Rail And Porterbrook To Showcase Britain’s Green Trains Of The Future At COP26.

These two paragraphs are from the end of the first section of the press release.

It is envisaged that the HydroFLEX may also be used to transport visitors to see the Zero Emission Train, Scotland’s first hydrogen powered train.

Network Rail is also in the earlier stages of planning a similar event with Vivarail to bring an operational battery train to COP26.

Vivarail have taken battery trains to Scotland before for demonstration, as I wrote about in Battery Class 230 Train Demonstration At Bo’ness And Kinneil Railway.

Will other train companies be joining the party?

Alstom

It looks like Alstom’s hydrogen-powered Class 600 train will not be ready for COP26.

But I suspect that the French would not like to be upstaged by a rolling stock leasing company and a university on the one hand and a company with scrapyard-ready redundant London Underground trains on the other.

I think, they could still turn up with something different.

They could drag one of their Coradia iLint trains through the Channel Tunnel and even run it to Scotland under hydrogen power, to demonstrate the range of a hydrogen-powered train.

Alstom have recently acquired Bombardier’s train interests in the UK and there have been rumours of a fleet of battery-electric Electrostars, even since the demonstrator ran successfully in 2015. Will the prototype turn up at COP26?

Alstom’s UK train factory is in Widnes and I’ve worked with Liverpudlians and Merseysiders on urgent projects and I wouldn’t rule out the Class 600 train making an appearance.

CAF

Spanish train company; CAF, have impressed me with the speed, they have setup their factory in Newport and have delivered a total of well over a hundred Class 195 and Class 331 trains to Northern.

I wrote Northern’s Battery Plans, in February 2020, which talked about adding a fourth-car to three-car Class 331 trains, to create a battery-electric Class 331 train.

Will the Spanish bring their first battery-electric Class 331 train to Glasgow?

I think, they just might!

After all, is there a better place for a train manufacturer looking to sell zero-carbon trains around the world to announce, their latest product?

Hitachi

A lot of what I have said for Alstom and CAF, could be said for Hitachi.

Hitachi have announced plans for two battery-electric trains; a Regional Battery Train and an Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train.

I doubt that either of these trains could be ready for COP26.

But last week, I saw the new Hitachi Class 803 train speeding through Oakleigh Park station.

This is not a battery-electric train, where battery power can be used for traction, but according to Wikipedia and other sources, it is certainly an electric train fitted with batteries to provide hotel power for the train, when the overhead electrification fails.

Are these Class 803 trains already fitted with their batteries? And if they are, have they been tested?

And who is building the batteries for the Class 803 trains?

The traction batteries for Hitachi’s two battery-electric trains are to be produced by Hyperdrive Innovation of Sunderland, which is not far from Hitachi’s train factory at Newton Aycliffe.

As an engineer, I would suspect that a well-respected company like Hyperdrive Innovation, can design a battery-pack that plugs in to Hitachi’s trains, as a diesel engine would. I would also suspect that a good design, would allow an appropriate size of battery for the application and route.

I feel it is very likely, that all batteries for Hitachi’s UK trains will be designed and build by Hyperdrive Innovation.

If that is the case and the Class 803 trains are fitted with batteries, then Hitachi can be testing the battery systems.

This document on the Hitachi Rail web site, which is entitled Development of Class 800/801 High-speed Rolling Stock for UK Intercity Express Programme, gives a very comprehensive description of the electrical and computer systems of the Hitachi trains.

As an engineer and a computer programmer, I believe that if Hyperdrive Innovation get their battery design right and after a full test program, that Hitachi could be able to run battery-electric trains based on the various Class 80x trains.

It could be a more difficult task to fit batteries to Scotland’s Class 385 trains, as they are not fitted with diesel engines in any application. Although, the fitting of diesel engines may be possible in the global specification for the train.

It is likely that these trains could form the basis of the Regional Battery Train, which is described in this infographic.

Note.

- The Class 385 and Regional Battery trains are both 100 mph trains.

- Class 385 and Class 80x trains are all members of Hitachi’s A-Train family.

- Regional Battery trains could handle a lot of unelectrified routes in Scotland.

I wouldn’t be surprised to see Hitachi bring a battery-equipped train to COP26, if the Class 803 trains have a successful introduction into service.

Siemens

Siemens have no orders to build new trains for the national rail network in the UK.

But there are plans by Porterbrook and possibly other rolling stock leasing companies and train operators to convert some redundant Siemens-built trains, like Class 350 trains, into battery-electric trains.

According to Wikipedia, Siemens upgraded East Midlands Railways, Class 360 trains to 110 mph operation, at their Kings Heath Depot in Northampton.

Could Siemens be updating one of the Class 350 trains, that are serviced at that depot, to a prototype battery-electric Class 350 train?

Stadler

Stadler have a proven design for diesel-electric, battery-electric and hydrogen trains, that they sell all over the world.

In the UK, the only ones in service are Greater Anglia’s Class 755 trains, which are diesel-electric bi-mode trains.

The picture shows one of these trains at Ipswich.

- They are 100 mph trains.

- Diesel, battery or hydrogen modules can be inserted in the short PowerPack car in the middle of the train.

- Diesel-battery-electric versions of these trains have been sold for operation in Wales.

- The interiors of these trains are designed for both short journeys and a two-hour run.

There is a possibility, that these trains will be upgraded with batteries. See Battery Power Lined Up For ‘755s’.

Conclusion

Times will be interesting in Glasgow at COP26!

What Would Be The Ultimate Range Of A Nine-Car Class 800 Train?

In Thoughts On Batteries On A Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train, I had a section, which was called The Ultimate Battery Train.

I said this.

I think it would be possible to put together a nine car battery-electric train with a long range.

- It would be based based on Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train technology, which would be applied to a Class 800 or Class 802 train.

- It would have two driver cars without batteries.

- It would have seven intermediate cars with 600 kWh batteries.

- It would have a total battery capacity of 4200 kWh.

- The train would be optimised for 100 mph running.

- My estimate in How Much Power Is Needed To Run A Train At 125 Or 100 mph?, said it would need 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile to cruise at 100 mph.

That would give a range of over 200 miles.

If the batteries were only 500 kWh, the range would be 178 miles.

Aberdeen, Inverness, Penzance and Swansea here we come.

Note that I have ignored energy lost in the station stops.

Energy Use And Recovery In A Station Stop

The station stop will be handled something like this.

The train will be happily trundling along at 100 mph.

At the right moment, the driver will apply the brakes and the train will stop in the station.

With trains like these Hitachi trains and many others, braking is performed by turning the traction motors into generators and the kinetic energy of the train will be turned into electricity.

Normally with this regenerative braking, the electricity is returned to the track, but these trains are not running on electrified track, so the electricity will be stored in the traction batteries on the train. This is often done in battery-electric road vehicles.

After the stop, the train will use battery power to accelerate back to 100 mph.

What kinetic energy will a Class 800 train have at 100 mph?

- The basic weight of a nine-car Class 800 train is 438 tonnes.

- I am assuming that the batteries are no heavier than the diesel engines they replace.

- The trains hold 611 passengers.

- I will assume each weighs 80 Kg with baggage, bikes and buggies, which gives a weight of 48.9 tonnes.

- This gives a total train weight of 486.9 tonnes.

Using Omni’s Kinetic Energy Calculator, gives a kinetic energy of 135.145 kWh.

When I first saw figures like this, I felt I had something wrong, but after checking time and time again, they still appear.

At each stop a proportion of the train’s kinetic energy will not be recovered.

These figures show the extra energy needed at each stop with different regenerative braking efficiencies.

- 100 % – 0 kWh

- 90 % – 13.51 kWh

- 80 % – 27.03 kWh

- 70 % – 40.54 kWh

- 60 % – 54.06 kWh

Obviously, the more efficient the regenerative braking, the less energy that needs to be added at each stop.

Edinburgh And Aberdeen

I am using Edinburgh and Aberdeen as an example.

Consider.

- I am assuming the train is cruising at 100 mph along the route.

- There are seven stations to the North of Haymarket station.

- If I assume 60 % regenerative braking efficiency, then each stop will need 54.06 kWh of electricity from the batteries.

- This gives a total of 378.4 kWh for the stops. Let’s call it 400 kWh.

- This effectively reduces the usable battery size to 3800 kWh

- Take off 200 kWh to make sure there’s always space for regenerative braking energy and useable battery size is 3600 kWh.

This can then be divided by the number of cars and 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile, to get the range.

This gives a range of over 180 miles.

With 500 kWh batteries the distance is just under 180 miles.

It certainly appears that a battery-electric train with seven 500-600 kWh batteries should be able to run between Edinburgh and Aberdeen.

Obviously, charging would be needed at Aberdeen.

What Would Be The Ultimate Range Of A Five-Car Class 800 Train?

What kinetic energy will a five-car Class 800 train have at 100 mph?

- The basic weight of a five-car Class 800 train is 243 tonnes.

- I am assuming that the batteries are no heavier than the diesel engines they replace.

- The trains hold 302 passengers.

- I will assume each weighs 80 Kg with baggage, bikes and buggies, which gives a weight of 25.6 tonnes.

- This gives a total train weight of 268.6 tonnes.

Using Omni’s Kinetic Energy Calculator, gives a kinetic energy of 74.6 kWh.

I will now use Edinburgh and Aberdeen as an example.

Consider.

- I am assuming the train is cruising at 100 mph along the route.

- I am assuming that the three intermediate cars have 600 kWh batteries.

- There are seven stations to the North of Haymarket station.

- If I assume 60 % regenerative braking efficiency, then each stop will need 29.84 kWh of electricity from the batteries.

- This gives a total of 208.9 kWh for the stops. Let’s call it 210 kWh.

- This effectively reduces the usable battery size to 1590 kWh

- Take off 100 kWh to make sure there’s always space for regenerative braking energy and useable battery size is 1490 kWh.

This can then be divided by the number of cars and 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile, to get the range.

This gives a range of over 136 miles.

With 500 kWh batteries the distance is around 110 miles.

It looks to me, that from these calculations that a nine-car train with battery packs in all the intermediate cars has a longer range than a five-car train with battery packs in all the intermediate cars.

What Would Be The Range Of a Five-Car Class 803 Train Equipped With Batteries?

What kinetic energy will a five-car Class 803 train have at 100 mph?

- The basic weight of a five-car Class 803 train is 228.5 tonnes.

- Three 600 kWh batteries could add 18 tonnes

- The trains hold 400 passengers.

- I will assume each weighs 80 Kg with baggage, bikes and buggies, which gives a weight of 32 tonnes.

- This gives a total train weight of 278.5 tonnes.

Using Omni’s Kinetic Energy Calculator, gives a kinetic energy of 77.3 kWh.

As before, I will now use Edinburgh and Aberdeen as an example.

Consider.

- I am assuming the train is cruising at 100 mph along the route.

- I am assuming that the three intermediate cars have 600 kWh batteries.

- There are seven stations to the North of Haymarket station.

- If I assume 60 % regenerative braking efficiency, then each stop will need 30.92 kWh of electricity from the batteries.

- This gives a total of 216.4 kWh for the stops. Let’s call it 220 kWh.

- This effectively reduces the usable battery size to 1580 kWh

- Take off 100 kWh to make sure there’s always space for regenerative braking energy and useable battery size is 1480 kWh.

This can then be divided by the number of cars and 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile, to get the range.

This gives a range of over 135 miles.

With 500 kWh batteries the distance is around 110 miles.

Thoughts On Batteries On A Hitachi Regional Battery Train

This article is a repeat of Thoughts On Batteries On A Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train, but for their other train with batteries; the Hitachi Regional Battery Train.

This Hitachi infographic describes a Hitachi Regional Battery Train.

Hitachi are creating the first of these battery trains, by replacing one of the diesel power-packs in a Class 802 train with a battery-pack from Hyperdrive Innovation of Sunderland.

The Class 802 train has the following characteristics.

- Five cars.

- Three diesel power-packs, each with a power output of 700 kW.

- 125 mph top speed on electricity.

- I believe all intermediate cars are wired for diesel power-packs, so can all intermediate cars have a battery?

In How Much Power Is Needed To Run A Train At 125 Or 100 mph?, I estimated that the trains need the following amounts of energy to keep them at a constant speed.

- Class 801 train – 125 mph 3.42 kWh per vehicle mile

- Class 801 train – 100 mph 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile

The figures are my best estimates.

We also know that according to Hitachi, the battery train has a range of 90 kilometres or 56 miles at a speed of 100 mph.

So applying the formula for energy needed gives that the battery size to cover 56 miles at a constant 100 mph will be.

56 * 2.19 * 5 = 613.2 kWh.

In the calculation for the Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mofr Battery Train, I had assumed that a 600 kWh battery was feasible, as it would lay less than the diesel engine it replaced.

I can also apply the formula for a four-car train.

56 * 2.19 * 4 = 490.6 kWh.

That too, would be very feasible.

Conclusion

I can’t wait to ride in one of Hitachi’s two proposed battery-electric trains.

Thoughts On Batteries On A Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train

This Hitachi infographic describes a Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train.

Hitachi are creating the first of these battery trains, by replacing one of the diesel power-packs in a Class 802 train with a battery-pack from Hyperdrive Innovation of Sunderland.

This press release from Hitachi is entitled Hitachi And Eversholt Rail To Develop GWR Intercity Battery Hybrid Train – Offering Fuel Savings Of More Than 20%, gives a few more details.

The Class 802 train has the following characteristics.

- Five cars.

- Three diesel power-packs, each with a power output of 700 kW.

- 125 mph top speed on electricity.

- I believe all intermediate cars are wired for diesel power-packs, so can all intermediate cars have a battery?

In How Much Power Is Needed To Run A Train At 125 Or 100 mph?, I estimated that the trains need the following amounts of energy to keep them at a constant speed.

- Class 801 train – 125 mph 3.42 kWh per vehicle mile

- Class 801 train – 100 mph 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile

The figures are my best estimates.

The Wikipedia entry for the Class 800 train, also gives the weight of the diesel power-pack and all its related gubbins.

The axle load of the train is given as 15 tonnes, but for a car without a diesel engine it is given as 13 tonnes.

As there are four axles to a car, I can deduce that the diesel power-pack and the gubbins, weigh around eight tonnes.

How much power would a one tonne battery hold?

This page on the Clean Energy institute at the University of Washington is entitled Lithium-Ion Battery.

This is a sentence from the page.

Compared to the other high-quality rechargeable battery technologies (nickel-cadmium or nickel-metal-hydride), Li-ion batteries have a number of advantages. They have one of the highest energy densities of any battery technology today (100-265 Wh/kg or 250-670 Wh/L).

Using these figures, a one-tonne battery would be between 100 and 265 kWh in capacity, depending on the energy density.

As it is likely that if the diesel power-pack replacement would probably leave things like fuel tanks and radiators behind, so that the diesel engines could be reinstalled, I would expect that a battery of around four tonnes would be fitted.

On the basis of the University of Washington’s figures a 400 kWh battery pack would certainly be feasible.

Using. the energy use at 100 mph of 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile, I can get the following ranges for different battery sizes.

- 400 kWh battery – 36.53 miles

- 500 kWh battery – 45.67 miles

- 600 kWh battery – 54.80 miles

- 800 kWh battery – 73.06 miles

As Lincoln and Newark are just 16.6 miles apart, it looks to me that a 500 or 600 kWh battery could be a good choice for that route, as it would leave enough hotel power for the turnround.

It should also handle shorter routes like these.

- Newbury and Bedwyn – 13.3 miles.

- Didcot and Oxford – 10.3 miles

- Newark and Lincoln – 16.6 miles

- Leeds and Harrogate – 18.3 miles

- Northallerton and Middlesbrough – 20 miles

- Hull and Temple Hirst Junction and Hull – 36.1 miles

Some routes like Temple Hirst Junction and Hull would need charging at the destination.

The Range Of A Five Car Train With Three Batteries

Suppose a Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train had three battery-packs and no diesel engines.

- It would be based on Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train technology.

- It would have two driver cars without batteries.

- It would have three intermediate cars with 600 kWh batteries.

- It would have 1800 kWh in the batteries.

- The train would be optimised for 100 mph running.

- My estimate says it would need 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile to cruise at 100 mph.

It could have a range of up to 164 miles.

If the batteries were only 500 kWh, the range would be 137 miles.

The Ultimate Battery Train

I think it would be possible to put together a nine car battery-electric train with a long range.

- It would be based based on Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train technology, which would be applied to a Class 800 or Class 802 train.

- It would have two driver cars without batteries.

- It would have seven intermediate cars with 600 kWh batteries.

- It would have a total battery capacity of 4200 kWh.

- The train would be optimised for 100 mph running.

- My estimate in How Much Power Is Needed To Run A Train At 125 Or 100 mph?, said it would need 2.19 kWh per vehicle mile to cruise at 100 mph.

That would give a range of over 200 miles.

If the batteries were only 500 kWh, the range would be 178 miles.

Aberdeen, Inverness, Penzance and Swansea here we come.

Can Hitachi Increase The Range Further?

There are various ways that the range can be improved.

- More electrically-efficient on-board systems like air-conditioning.

- A more aerodynamic nose.

- Regenerative braking to the batteries.

- Batteries with a higher energy density.

- Better driver assistance software.

Note.

- Hitachi have already announced that the Class 810 trains for East Midlands Railway will have a new nose profile.

- Batteries are improving all the time.

I wouldn’t be surprised to see a ten percent improvement in range by 2030.

Conclusion

I was surprised at some of the results of my estimates.

But I do feel that Hitachi trains with 500-600 kWh batteries could bring a revolution to train travel in the UK.

Edinburgh And Aberdeen

Consider.

- The gap in the electrification is 130 miles between Edinburgh Haymarket and Aberdeen.

- There could be an intermediate charging station at Dundee.

- Charging would be needed at Aberdeen.

I think Hitachi could design a train for this route.

Edinburgh And Inverness

Consider.

- The gap in the electrification is 146 miles between Stirling and Inverness.

- This could be shortened by 33 miles, if there were electrification between Stirling and Perth.

- Charging would be needed at Inverness.

I think Hitachi could design a train for this route.

DfT To Have Final Say On Huddersfield Rebuild Of Rail Station And Bridges

The title of this post, is the same as that of this article on Rail Technology Magazine.

This is the first paragraph.

As part of the £1.4bn Transpennine Route Upgrade. Transport Secretary Grant Shapps is to rule on planned changes to Huddersfield’s 19th century rail station and not the Kirklees council, in what is to be a huge revamp of the line between Manchester and York.

According to the article eight bridges are to be replaced or seriously modified.

As Huddersfield station (shown) is Grade I listed and three other Grade II listed buildings and structures are involved, I can see this project ending up with a substantial bill for lawyers.

But then, to have a world-class railway across the Pennines, a few eggs will need to be broken.

Electric Trains Across The Pennine

This page on the Network Rail web site describes the Huddersfield To Westtown (Dewsbury) Upgrade.

When the upgrade and the related York To Church Fenton Improvement Scheme is completed, the TransPennine route between Huddersfield and York will be fully-electrified.

As Manchester To Stalybridge will also have been electrified, this will mean that the only section without electrification will be the eighteen miles across the Pennines between Stalybridge and Huddersfield.

Will this final eighteen miles ne electrified?

Eighteen miles with electrification at both ends will be a short jump for a Hitachi Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train, the specification of which is shown in this Hitachi infographic.

The Class 802 trains of TransPennine Express are able to be converted into these trains.

The trains could work these routes.

- Liverpool Lime Street and Scarborough

- Manchester Airport and Redcar

- Liverpool Lime Street and Edinburgh via Newcastle

- Manchester Airport and Newcastle

- Manchester Piccadilly and Hull

- Manchester Airport and Cleethorpes

Note.

- I suspect some more Class 802 trains with batteries will be needed.

- The trains would either use battery or diesel power to reach Hull, Redcar and Scarborough or there could be a few miles of electrification to stretch battery range.

- Will the Class 68 diesel locomotives be replaced with Class 93 tri-mode locomotives to haul the Mark 5A coaches to Scarborough.

- Manchester Airport and Cleethorpes could be a problem and will probably need some electrification around Sheffield and Grimsby.

This would just mean TransPennine’s two short routes to be decarbonised.

- Manchester Piccadilly and Huddersfield

- Huddersfield and Leeds

As except for the eighteen mile gap between Stalybridge and Huddersfield, these two routes are fully-electrified, I suspect that a battery-electric version of a 110 mph electric train like a Class 387 or Class 350 train could run these routes.

Conclusion

It looks like if these sections of the TransPennine Express network are upgraded and electrified.

- York and Church Fenton

- Huddersfield and Westtown

- Manchester and Staylebridge

Together with a few extra miles of electrification at strategic points, that TransPennine Express will be able to decarbonise.

What Is Possible On The East Coast Main Line?

In the Wikipedia entry for the Class 91 locomotive, there is an amazing story.

This picture shows one of these locomotives at Kings Cross.

Note.

- They have a design speed of 140 mph.

- They have a power output of 4.8 MW.

- They were built around 1990 by British Rail at Crewe.

They were designed to run services between London King’s Cross and Edinburgh as fast as possible, as the motive power of the InterCity 225 trains.

This section in the Wikipedia entry for the Class 91 locomotive is entitled Speed Record. This is the first paragraph.

A Class 91, 91010 (now 91110), holds the British locomotive speed record at 161.7 mph (260.2 km/h), set on 17 September 1989, just south of Little Bytham on a test run down Stoke Bank with the DVT leading. Although Class 370s, Class 373s and Class 374s have run faster, all are EMUs which means that the Electra is officially the fastest locomotive in Britain. Another loco (91031, now 91131), hauling five Mk4s and a DVT on a test run, ran between London King’s Cross and Edinburgh Waverley in 3 hours, 29 minutes and 30 seconds on 26 September 1991. This is still the current record. The set covered the route in an average speed of 112.5 mph (181.1 km/h) and reached the full 140 mph (225 km/h) several times during the run.

Note.

- For the British locomotive speed record, locomotive was actually pushing the train and going backwards, as the driving van trailer (DVT) was leading.

- How many speed records of any sort, where the direction isn’t part of the record, have been set going backwards?

- I feel that this record could stand for many years, as it is not very likely anybody will build another 140 mph locomotive in the foreseeable future. Unless a maverick idea for a high speed freight locomotive is proposed.

I have a few general thoughts on the record run between Kings Cross and Edinburgh in three-and-a-half hours.

- I would assume that as in normal operation of these trains, the Class 91 locomotive was leading on the run to the North.

- For various reasons, they would surely have had at least two of British Rail’s most experienced drivers in the cab.

- At that time, 125 mph InterCity 125 trains had been the workhorse of East Coast Main Line for well over ten years, so British Rail wouldn’t have been short of experienced high speed drivers.

- It was a Thursday, so they must have been running amongst normal traffic.

- On Monday, a typical run between Kings Cross and Edinburgh is timetabled to take four hours and twenty minutes.

- High Speed Two are predicting a time of three hours and forty-eight minutes between Euston and Edinburgh via High Speed Two and the West Coast Main Line.

The more you look at it, a sub-three-and-and-a-half hour time, by 1980s-technology on a less-than-perfect railway was truly remarkable.

So how did they do it?

Superb Timetabling

In Norwich-In-Ninety Is A Lot More Than Passengers Think!, I talk about how Network Rail and Greater Anglia created a fast service between Liverpool Street and Norwich.

I suspect that British Rail put their best timetablers on the project, so that the test train could speed through unhindered.

Just as they did for Norwich-in-Ninety and probably will be doing to the East Coast Main Line to increase services and decrease journey times.

A Good As ERTMS Signalling

Obviously in 1991, there was no modern digital in-cab signalling and I don’t know the standard of communication between the drivers and the signallers.

On the tricky sections like Digswell Viaduct, through Hitchin and the Newark Crossing were other trains stopped well clear of any difficult area, as modern digital signalling can anticipate and take action?

I would expect the test train got a signalling service as good as any modern train, even if parts of it like driver to signaller communication may have been a bit experimental.

There may even have been a back-up driver in the cab with the latest mobile phone.

It must have been about 1991, when I did a pre-arranged airways join in my Cessna 340 on the ground at Ipswich Airport before take-off on a direct flight to Rome. Air Traffic Control had suggested it to avoid an intermediate stop at say Southend.

The technology was arriving and did it help the drivers on that memorable run North ensure a safe and fast passage of the train?

It would be interesting to know, what other equipment was being tested by this test train.

A Possible Plan

I suspect that the plan in 1991 was to use a plan not unlike one that would be used by Lewis Hamilton, or in those days Stirling Moss to win a race.

Drive a steady race not taking any chances and where the track allows speed up.

So did British Rail drive a steady 125 mph sticking to the standard timetable between Kings Cross and Edinburgh?

Then as the Wikipedia extract indicated, at several times during the journey did they increase the speed of the train to 140 mph.

And the rest as they say was an historic time of 3 hours, 29 minutes and 30 seconds. Call it three-and-a-half-hours.

This represented a start-to-stop average speed of 112.5 mph over the 393 miles of the East Coast Main Line.

Can The Current Trains Achieve Three-And-A-Half-Hours Be Possible Today?

Consider.

- The best four hours and twenty minutes timings of the Class 801 trains, represents an average speed of 90.7 mph.

- The Class 801 trains and the InterCity 225 trains have similar performance.

- There have been improvements to the route like the Hitchin Flyover.

- Full ERTMS in-cab signalling is being installed South of Doncaster.

- I believe ERTMS and ETC could solve the Newark Crossing problem! See Could ERTMS And ETCS Solve The Newark Crossing Problem?

- I am a trained Control Engineer and I believe if ERTMS and ETC can solve the Newark Crossing problem, I suspect they can solve the Digswell Viaduct problem.

- The Werrington Dive Under is being built.

- The approaches to Kings Cross are being remodelled.

I can’t quite say easy-peasy. but I’m fairly certain the Kings Cross and Edinburgh record is under serious threat.

- A massive power supply upgrade to the North of Doncaster is continuing. See this page on the Network Rail web site.

- ERTMS and ETC probably needs to be installed all the way between Kings Cross and Edinburgh.

- There may be a need to minimise the number of slower passenger trains on the East Coast Main Line.

- The Northumberland Line and the Leamside Line may be needed to take some trains from the East Coast Main Line.

Recent Developments Concerning the Hitachi Trains

There have been several developments since the Hitachi Class 800 and Class 801 trains were ordered.

- Serious engineers and commentators like Roger Ford of Modern Railways have criticised the lugging of heavy diesel engines around the country.

- Network Rail have upgraded the power supply South of Doncaster and have recently started to upgrade it between Doncaster and Edinburgh. Will this extensive upgrade cut the need to use the diesel power-packs?

- Hitachi and their operators must have collected extensive in-service statistics about the detailed performance of the trains and the use of the diesel power-packs.

- Hitachi have signed an agreement with Hyperdrive Innovation of Sunderland to produce battery-packs for the trains and two new versions of the trains have been announced; a Regional Battery Train and an Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train.

- East Coast Trains have ordered five five-car Class 803 trains, each of which will have a small battery for emergency use and no diesel power-packs.

- Avanti West Coast have ordered ten seven-car Class 807 trains, each of which have no battery or diesel power-packs.

And these are just the ones we know about.

The Class 807 Trains And Liverpool

I find Avanti West Coast’s Class 807 trains the most interesting development.

- They have been partly financed by Rock Rail, who seem to organise train finance, so that the train operator, the train manufacturer all get the best value, by finding good technical solutions.

- I believe that these trains have been designed so they can run between Euston and Liverpool Lime Street stations in under two hours.

- Does the absence of battery or diesel power-packs save weight and improve performance?

- Euston and Liverpool Lime Street in two hours would be an average of only 96.8 mph.

- If the Class 807 trains could achieve the same start-stop average of 112.5 mph achieved by the InterCity 225 test run between Kings Cross and Edinburgh, that would mean a Euston and Liverpool Lime Street time of one hour and forty-three minutes.

- Does Thunderbird provision on the West Coast Main Line for the Class 390 trains mean that the Class 807 trains don’t need emergency power?

- Have diesel power-packs been rarely used in emergency by the Hitachi trains?

I believe the mathematics show that excellent sub-two hour times between Euston and Liverpool Lime Street are possible by Avanti West Coast’s new Class 807 trains.

The Class 803 Trains And Edinburgh

East Coast Trains ordered their Class 803 trains in March 2019, nine months before Avanti West Coast ordered their Class 807 trains.

In Trains Ordered For 2021 Launch Of ‘High-Quality, Low Fare’ London – Edinburgh Service, I outlined brief details of the trains and the proposed service.

- FirstGroup is targeting the two-thirds of passengers, who fly between London and Edinburgh.

- They are also targeting business passengers, as the first train arrives in Edinburgh at 10:00.

- The trains are five-cars.

- The trains are one class with onboard catering, air-conditioning, power sockets and free wi-fi.

- Stops will be five trains per day with stops at Stevenage, Newcastle and Morpeth.

- The trains will take around four hours.

- The service will start in Autumn 2021.

I also thought it would be a successful service

As I know Edinburgh, Liverpool and London well, I believe there are similarities between the Euston-Liverpool Lime Street and Kings Cross-Edinburgh routes.

- Both routes are between two cities known all over the world.

- Both routes are fully-electrified.

- Both routes have the potential to attract passengers from other transport modes.

The two services could even be run at similar speeds.

- Euston-Liverpool Lime Street in two hours will be at 96.8 mph

- Kings Cross-Edinburgh in four hours will be at 98.3 mph.

Does this explain the similar lightweight trains?

Could Lightweight Trains Help LNER?

There is one important factor, I haven’t talked about in detail in this post. Batteries and diesel power-packs on the Hitachi trains.

I have only mentioned them in the following circumstances.

- When trains are not fitted with battery and/or diesel power-packs.

- When battery developments are being undertaken.

Let’s consider the LNER fleet.

- LNER has thirteen nine-car Class 800 trains, each of which has five diesel power-packs

- LNER has ten five-car Class 800 trains, each of which has three diesel power-packs

- LNER has thirty nine-car Class 801 trains, each of which has one diesel power-pack

- LNER has twelve five-car Class 801 trains, each of which has one diesel power-pack

There are sixty-five trains, 497 coaches and 137 diesel power-packs.

And look at their destinations.

- Aberdeen – No Electrification from Edinburgh

- Alnmouth – Fully Electrified

- Berwick-upon-Tweed – Fully Electrified

- Bradford Forster Square – Fully Electrified

- Darlington – Fully Electrified

- Doncaster – Fully Electrified

- Durham – Fully Electrified

- Edinburgh – Fully Electrified

- Glasgow – Fully Electrified

- Grantham – Fully Electrified

- Harrogate – No Electrification from Leeds – Possible Battery Destination

- Huddersfield – No Electrification from Leeds – Possible Battery Destination – Probable Electrification

- Hull – No Electrification from Temple Hirst Junction – Possible Battery Destination

- Inverness – No Electrification from Stirling

- Leeds – Fully Electrified

- Lincoln – No Electrification from Newark North Gate – Possible Battery Destination

- Middlesbrough – No Electrification from Northallerton – Possible Battery Destination

- Newcastle – Fully Electrified

- Newark North Gate – Fully Electrified

- Northallerton – Fully Electrified

- Peterborough – Fully Electrified

- Skipton – Fully Electrified

- Retford – Fully Electrified

- Stevenage – Fully Electrified

- Stirling – Fully Electrified

- Sunderland – No Electrification from Northallerton – Possible Battery Destination

- Wakefield Westgate – Fully Electrified

- York – Fully Electrified

The destinations can be summarised as followed.

- Not Electrified – 2

- Possible Battery Destination – 6

- Fully Electrified – 20

This gives a total of 28.

Could the trains be matched better to the destinations?

- Some routes like Edinburgh, Glasgow, Newcastle and Stirling could possibly be beneficially handled by lightweight trains without any diesel or battery power-packs.

- Only Aberdeen and Inverness can’t be reached by all-electric or battery-electric trains.

- In LNER Seeks 10 More Bi-Modes, I proposed a hydrogen-electric flagship train, that would use hydrogen North of the existing electrification.

There certainly appear to be possibilities.

Example Journey Times To Edinburgh

This table shows the various time for particular start-stop average speeds between Kings Cross and Edinburgh.

- 80 mph – 4:54

- 85 mph – 4:37

- 90 mph – 4:12

- 98.2 mph – 4:00

- 100 mph – 3:56

- 110 mph – 3:34

- 120 mph – 3:16

- 125 mph – 3:08

Note.

- Times are given in h:mm.

- A few mph increase in average speed reduces journey time by a considerable amount.

The figures certainly show the value of high speed trains and of removing bottlenecks, as average speed is so important.

Decarbonisation Of LNER

LNER Seeks 10 More Bi-Modes was based on an article in the December 2020 Edition of Modern Railways, with the same title. These are the first two paragraphs of the article.

LNER has launched the procurement of at least 10 new trains to supplement its Azuma fleet on East Coast main line services.

In a Prior Information Notice published on 27 October, the operator states it is seeking trains capable of operating under 25kW overhead power with ‘significant self-power capability’ for operation away from overhead wires. ‘On-board Energy Storage for traction will be specified as a mandatory requirement to reduce, and wherever practical eliminate, diesel usage where it would otherwise be necessary, although LNER anticipates some degree of diesel traction may be required to meet some self-power requirements. Suppliers tendering are asked to detail their experience of designing and manufacturing a fleet of multi-mode trains with a range of traction options including battery-electric, diesel-electric, hydrogen-electric, battery-diesel, dual fuel and tri-mode.

From this, LNER would appear to be serious about decarbonisation and from the destination list I published earlier, most services South of the Scottish Central Belt can be decarbonised by replacing diesel-power packs with battery power-packs.

That last bit, sounds like a call for innovation to provide a solution to the difficult routes to Aberdeen and Inverness. It also looks as if it has been carefully worded not to rule anybody out.

This press release from Hitachi is entitled Hitachi And Eversholt Rail To Develop GWR Intercity Battery Hybrid Train – Offering Fuel Savings Of More Than 20%.

It announces the Hitachi Intercity Tri-mode Battery Train, which is described in this Hitachi infographic.

As the Hitachi press release is dated the 15th of December 2020, which is after the publication of the magazine, it strikes me that LNER and Hitachi had been talking.

At no point have Hitachi stated what the range of the train is on battery power.

To serve the North of Scotland these gaps must be bridged.

- Aberdeen and Edinburgh Haymarket – 130 miles

- Inverness and Stirling – 146 miles

It should also be noted that distances in Scotland are such, that if these gaps could be bridged by battery technology, then probably all of the North of Scotland’s railways could be decarbonised. As Hitachi are the major supplier of Scotland’s local and regional electric trains, was the original Prior Information Notice, written to make sure Hitachi responded?

LNER run nine-car Class 800 trains on the two long routes to Aberdeen and Inverness.

- These trains have five diesel power-packs under coaches 2,3, 5, 7 and 8.

- As five-car Class 800 trains have diesel power-packs under coaches 2, 3 and 4, does this mean that Hitachi can fit diesel power-packs under all cars except for the driver cars?

- As the diesel and battery power-packs appear to be interchangeable, does this mean that Hitachi could theoretically build some very unusual trains?

- Hitachi’s trains can be up to twelve-cars in normal mode and twenty-four cars in rescue mode.

- LNER would probably prefer an all Azuma fleet, even if a few trains were a bit longer.

Imagine a ten-car train with two driver and eight intermediate cars, with all of the intermediate cars having maximum-size battery-packs.

Supposing, one or two of the battery power-packs were to be replaced with a diesel power-pack.

There are a lot of possibilities and I suspect LNER, Hitachi and Hyperdrive Innovation are working on a train capable of running to and from the North of Scotland.

Conclusion

I started by asking what is possible on The East Coast Main Line?

As the time of three-and-a-half hours was achieved by a short-formation InterCity 225 train in 1991 before Covids, Hitchin, Kings Cross Remodelling, Power Upgrades, Werrington and lots of other work, I believe that some journeys between Kings Cross and Edinburgh could be around this time within perhaps five years.

To some, that might seem an extraordinary claim, but when you consider that the InterCity 225 train in 1991 did it with only a few sections of 140 mph running, I very much think it is a certainly at some point.

As to the ultimate time, earlier I showed that an average of 120 mph between King’s Cross and Edinburgh gives a time of 3:16 minutes.

Surely, an increase of fourteen minutes in thirty years is possible?

High-Speed Low-Carbon Transport Between Great Britain And Ireland

Consider.

- According to Statista, there were 13,160,000 passengers between the United Kingdom and the Irish Republic in 2019.

- In 2019, Dublin Airport handled 32,907,673 passengers.

- The six busiest routes from Dublin were Heathrow, Stansted, Amsterdam, Manchester, Birmingham and Stansted.

- In 2018, Belfast International Airport handled 6,269,025 passengers.

- The four busiest routes from Belfast International Airport were Stansted, Gatwick. Liverpool and Manchester, with the busiest route to Europe to Alicante.

- In 2018, Belfast City Airport handled 2,445,529 passengers.

- The four busiest routes from Belfast City Airport were Heathrow, Manchester, Birmingham and London City.

Note.

- The busiest routes at each airport are shown in descending order.

- There is a lot of air passengers between the two islands.

- Much of the traffic is geared towards London’s four main airports.

- Manchester and Liverpool get their fair share.

Decarbonisation of the air routes between the two islands will not be a trivial operation.

But technology is on the side of decarbonisation.

Class 805 Trains

Avanti West Coast have ordered thirteen bi-mode Class 805 trains, which will replace the diesel Class 221 trains currently working between London Euston and Holyhead.

- They will run at 125 mph between Euston and Crewe using electric power.

- If full in-cab digital signalling were to be installed on the electrified portion of the route, they may be able to run at 140 mph in places under the wires.

- They will use diesel power on the North Wales Coast Line to reach Holyhead.

- According to an article in Modern Railways, the Class 805 trains could be fitted with batteries.

I wouldn’t be surprised that when they are delivered, they are a version of the Hitachi’s Intercity Tri-Mode Battery Train, the specification of which is shown in this Hitachi infographic.

Note.

- I suspect that the batteries will be used to handle regenerative braking on lines without electrification, which will save diesel fuel and carbon emissions.

- The trains accelerate faster, than those they replace.

- The claimed fuel and carbon saving is twenty percent.

It is intended that these trains will be introduced next year.

I believe that, these trains will speed up services between London Euston and Holyhead.

- Currently, services take just over three-and-a-half hours.

- There should be time savings on the electrification between London Euston and Crewe.

- The operating speed on the North Wales Coast Line is 90 mph. This might be increased in sections.

- Some extra electrification could be added, between say Crewe and Chester and possibly through Llandudno Junction.

- I estimate that on the full journey, the trains could reduce emissions by up to sixty percent compared to the current diesel trains.

I think that a time of three hours could be achievable with the Class 805 trains.

New trains and a three hour journey time should attract more passengers to the route.

Holyhead

In Holyhead Hydrogen Hub Planned For Wales, I wrote about how the Port of Holyhead was becoming a hydrogen hub, in common with several other ports around the UK including Felixstowe, Harwich, Liverpool and Portsmouth.

Holyhead and the others could host zero-carbon hydrogen-powered ferries.

But this extract from the Wikipedia hints at work needed to be done to create a fast interchange between trains and ferries.

There is access to the port via a building shared with Holyhead railway station, which is served by the North Wales Coast Line to Chester and London Euston. The walk between trains and ferry check in is less than two minutes, but longer from the remote platform 1, used by Avanti West Coast services.

This Google Map shows the Port of Holyhead.

I think there is a lot of potential to create an excellent interchange.

HSC Francisco

I am using the high-speed craft Francisco as an example of the way these ships are progressing.

- Power comes from two gas-turbine engines, that run on liquified natural gas.

- It can carry 1024 passengers and 150 cars.

- It has a top speed of 58 knots or 67 mph. Not bad for a ship with a tonnage of over 7000.

This ship is in service between Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

Note.

- A craft like this could be designed to run on zero-carbon liquid hydrogen or liquid ammonia.

- A high speed craft already runs between Dublin and Holyhead taking one hour and forty-nine minutes for the sixty-seven miles.

Other routes for a specially designed high speed craft might be.

- Barrow and Belfast – 113 miles

- Heysham and Belfast – 127 miles

- Holyhead and Belfast – 103 miles

- Liverpool and Belfast – 145 miles

- Stranraer and Larne – 31 miles

Belfast looks a bit far from England, but Holyhead and Belfast could be a possibility.

London And Dublin Via Holyhead

I believe this route is definitely a possibility.

- In a few years, with a few improvements on the route, I suspect that London Euston and Holyhead could be fairly close to three hours.

- With faster bi-mode trains, Manchester Airport and Holyhead would be under three hours.

- I would estimate, that a high speed craft built for the route could be under two hours between Holyhead and Dublin.

It certainly looks like London Euston and Dublin and Manchester Airport and Dublin would be under five hours.

In A Glimpse Of 2035, I imagined what it would be like to be on the first train between London and Dublin via the proposed fixed link between Scotland and Northern Ireland.

- I felt that five-and-a-half hours was achievable for that journey.

- The journey would have used High Speed Two to Wigan North Western.

- I also stated that with improvements, London and Belfast could be three hours and Dublin would be an hour more.

So five hours between London Euston and Dublin using current technology without massive improvements and new lines could be small change well spent.

London And Belfast Via Holyhead

At 103 miles the ferry leg may be too long for even the fastest of the high speed craft, but if say the craft could do Holyhead and Belfast in two-and-a-half hours, it might just be a viable route.

- It might also be possible to run the ferries to a harbour like Warrenpoint, which would be eighty-six miles.

- An estimate based on the current high speed craft to Dublin, indicates a time of around two hours and twenty minutes.

It could be viable, if there was a fast connection between Warrenpoint and Belfast.

Conclusion

Once the new trains are running between London Euston and Holyhead, I would expect that an Irish entrepreneur will be looking to develop a fast train and ferry service between England and Wales, and the island of Ireland.

It could be sold, as the Greenest Way To Ireland.

Class 807 Trains

Avanti West Coast have ordered ten electric Class 807 trains, which will replace some of the diesel Class 221 trains.

- They will run at 125 mph between Euston and Liverpool on the fully-electrified route.

- If full in-cab digital signalling were to be installed on the route, they may be able to run at 140 mph in places.

- These trains appear to be the first of the second generation of Hitachi trains and they seem to be built for speed and a sparking performance,

- These trains will run at a frequency of two trains per hour (tph) between London and Liverpool Lime Street.

- Alternate trains will stop at Liverpool South Parkway station.

In Will Avanti West Coast’s New Trains Be Able To Achieve London Euston and Liverpool Lime Street In Two Hours?, I came to the conclusion, that a two-hour journey time was possible, when the new Class 807 trains have entered service.

London And Belfast Via Liverpool And A Ferry

Consider.

- An hour on the train to and from London will be saved compared to Holyhead.

- The ferry terminal is in Birkenhead on the other side of the Mersey and change between Lime Street station and the ferry could take much longer than at Holyhead.

- Birkenhead and Belfast is twice the distance of Holyhead and Dublin, so even a high speed craft would take three hours.

This Google Map shows the Ferry Terminal and the Birkenhead waterfront.

Note.

- The Ferry Terminal is indicated by the red arrow at the top of the map.

- There are rows of trucks waiting for the ferries.

- In the South East corner of the map, the terminal of the Mersey Ferry sticks out into the River

- Hamilton Square station is in-line with the Mersey Ferry at the bottom of the map and indicated with the usual red symbol.

- There is a courtesy bus from Hamilton Square station to the Ferry Terminal for Ireland.

There is a fourteen tph service between Hamilton Square and Liverpool Lime Street station.

This route may be possible, but the interchange could be slow and the ferry leg is challenging.

I don’t think the route would be viable unless a much faster ferry is developed. Does the military have some high speed craft under development?

Conclusion

London and Belfast via Liverpool and a ferry is probably a trip for enthusiasts or those needing to spend a day in Liverpool en route.

Other Ferry Routes

There are other ferry routes.

Heysham And Barrow-in-Furness

,These two ports might be possible, but neither has a good rail connection to London and the South of England.

They are both rail connected, but not to the standard of the connections at Holyhead and Liverpool.

Cairnryan

The Cairnryan route could probably be improved to be an excellent low-carbon route to Glasgow and Central Scotland.

Low-Carbon Flight Between The Islands Of Great Britain And Ireland

I think we’ll gradually see a progression to zero-carbon flight over the next few years.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Obviously zero-carbon would be better, but until zero-carbon aircraft are developed, there is always sustainable aviation fuel.

This can be produced from various carbon sources like biowaste or even household rubbish and disposable nappies.

British Airways are involved in a project called Altalto.

- Altalto are building a plant at Immingham to turn household rubbish into sustainable aviation fuel.

- This fuel can be used in jet airliners with very little modification of the aircraft.

I wrote about Altalto in Grant Shapps Announcement On Friday.

Smaller Low-Carbon Airliners

The first low- and zero-carbon airliners to be developed will be smaller with less range, than Boeing 737s and Airbus A 320s. These three are examples of four under development.

- Aura Aero Era – 19 passengers – 500 miles

- Eviation Alice – 9 passengers – 620 miles

- Faradair Aerospace BEHA – 19 passengers – 1150 miles

- Heart Aerospace ES-19 – 19 passengers – 400 km.

I feel that a nineteen seater aircraft with a range of 500 miles will be the first specially designed low- or zero-carbon airliner to be developed.

I believe these aircraft will offer advantages.

- Some routes will only need refuelling at one end.

- Lower noise and pollution.

- Some will have the ability to work from short runways.

- Some will be hybrid electric running on sustainable aviation fuel.

They may enable passenger services to some smaller airports.

Air Routes Between The Islands Of Great Britain And Ireland

These are distances from Belfast City Airport.

- Aberdeen – 228 miles

- Amsterdam – 557 miles

- Birmingham – 226 miles

- Blackpool – 128 miles

- Cardiff – 246 miles

- Edinburgh – 135 miles

- Gatwick – 337 miles

- Glasgow – 103 miles

- Heathrow – 312 miles

- Jersey – 406 miles

- Kirkwall – 320 miles

- Leeds – 177 miles

- Liverpool – 151 miles

- London City – 326 miles

- Manchester – 170 miles

- Newcastle – 168 miles

- Southampton – 315 miles

- Southend – 344 miles

- Stansted – 292 miles

- Sumburgh – 401 miles

Note.

- Some airports on this list do not currently have flights from Belfast City Airport.

- I have included Amsterdam for comparison.

- Distances to Belfast International Airport, which is a few miles to the West of Belfast City Airport are within a few miles of these distances.

It would appear that much of Great Britain is within 500 miles of Belfast City Airport.

These are distances from Dublin Airport.

- Aberdeen – 305 miles

- Amsterdam – 465 miles

- Birmingham – 199 miles

- Blackpool – 133 miles

- Cardiff – 185 miles

- Edinburgh – 208 miles

- Gatwick – 300 miles

- Heathrow – 278 miles

- Jersey – 339 miles

- Kirkwall – 402 miles

- Leeds – 190 miles

- Liverpool – 140 miles

- London City – 296 miles

- Manchester – 163 miles

- Newcastle – 214 miles

- Southampton – 268 miles

- Southend – 319 miles

- Stansted – 315 miles

- Sumburgh – 483 miles

Note.

- Some airports on this list do not currently have flights from Dublin Airport.

- I have included Amsterdam for comparison.

It would appear that much of Great Britain is within 500 miles of Dublin Airport.

I will add a few long routes, that someone might want to fly.

- Cork and Aberdeen – 447 miles

- Derry and Manston – 435 miles

- Manston and Glasgow – 392 miles

- Newquay and Aberdeen – 480 miles

- Norwich and Stornaway – 486 miles.

I doubt there are many possible air services in the UK and Ireland that are longer than 500 miles.

I have a few general thoughts about low- and zero-carbon air services in and around the islands of Great Britain and Ireland.

- The likely five hundred mile range of the first generation of low- and zero-carbon airliners fits the size of the these islands well.

- These aircraft seem to have a cruising speed of between 200 and 250 mph, so flight times will not be unduly long.

- Airports would need to have extra facilities to refuel or recharge these airliners.

- Because of their size, there will need to be more flights on busy routes.

- Routes which are less heavily used may well be developed, as low- or zero-carbon could be good for marketing the route.

I suspect they could be ideal for the development of new routes and even new eco-friendly airports.

Conclusion

I have come to the conclusion, that smaller low- or zero-carbon are a good fit for the islands of Great Britain and Ireland.

But then Flybe and Loganair have shown that you can make money flying smaller planes around these islands with the right planes, airports, strategy and management.

Hydrogen-Powered Planes From Airbus

Hydrogen-powered zero-carbon aircraft could be the future and Airbus have put down a marker as to the way they are thinking.

Airbus have proposed three different ZEROe designs, which are shown in this infographic.

The turboprop and the turbofan will be the type of designs, that could be used around Great Britain and Ireland.

The ZEROe Turboprop

This is Airbus’s summary of the design for the ZEROe Turboprop.

Two hybrid hydrogen turboprop engines, which drive the six bladed propellers, provide thrust. The liquid hydrogen storage and distribution system is located behind the rear pressure bulkhead.

This screen capture taken from the video, shows the plane.

It certainly is a layout that has been used successfully, by many conventionally-powered aircraft in the past. The De Havilland Canada Dash 8 and ATR 72 are still in production.

I don’t think the turboprop engines, that run on hydrogen will be a problem.

If you look at the Lockheed-Martin C 130J Super Hercules, you will see it is powered by four Rolls-Royce AE 2100D3 turboprop engines, that drive 6-bladed Dowty R391 composite constant-speed fully-feathering reversible-pitch propellers.

These Rolls-Royce engines are a development of an Allison design, but they also form the heart of Rolls-Royce’s 2.5 MW Generator, that I wrote about in Our Sustainability Journey. The generator was developed for use in Airbus’s electric flight research program.

I wouldn’t be surprised to find the following.

- , The propulsion system for this aircraft is under test with hydrogen at Derby and Toulouse.

- Dowty are testing propellers suitable for the aircraft.

- Serious research is ongoing to store enough liquid hydrogen in a small tank that fits the design.

Why develop something new, when Rolls-Royce, Dowty and Lockheed have done all the basic design and testing?

This screen capture taken from the video, shows the front view of the plane.

From clues in the picture, I estimate that the fuselage diameter is around four metres. Which is not surprising, as the Airbus A320 has a height of 4.14 metres and a with of 3.95 metres. But it’s certainly larger than the fuselage of an ATR-72.

So is the ZEROe Turboprop based on a shortened Airbus A 320 fuselage?

- The ATR 72 has a capacity of 70 passengers.

- The ZEROe Turboprop has a capacity of less than a hundred passengers.

- An Airbus A320 has six-abreast seating.

- Could the ZEROe Turboprop have sixteen rows of seats, as there are sixteen windows in front of the wing?

- With the seat pitch of an Airbus A 320, which is 81 centimetres, this means just under thirteen metres for the passengers.

- There could be space for a sizeable hydrogen tank in the rear part of the fuselage.

- The plane might even be able to use the latest A 320 cockpit.

It looks to me, that Airbus have designed a larger ATR 72 based on an A 320 fuselage.

I don’t feel there are any great technical challenges in building this aircraft.

- The engines appear to be conventional and could even have been more-or-less fully developed.

- The fuselage could be a development of an existing design.

- The wings and tail-plane are not large and given the company’s experience with large composite structures, they shouldn’t be too challenging.

- The hydrogen storage and distributing system will have to be designed, but as hydrogen is being used in increasing numbers of applications, I doubt the expertise will be difficult to find.

- The avionics and other important systems could probably be borrowed from other Airbus products.

Given that the much larger and more complicated Airbus A380 was launched in 2000 and first flew in 2005, I think that a prototype of this aircraft could fly around the middle of this decade.

It may seem small at less than a hundred seats, but it does have a range of greater than a 1000 nautical miles or 1150 miles.

Consider.

- It compares closely in passenger capacity, speed and range, with the De Havilland Canada Dash 8/400 and the ATR 72/600.

- The ATR 72 is part-produced by Airbus.

- The aircraft is forty percent slower than an Airbus A 320.

- It looks like it could be designed to have a Short-Takeoff-And Landing (STOL) capability.

I can see the aircraft replacing Dash 8s, ATR 72s and similar aircraft all over the world. There are between 2000 and 3000 operational airliners in this segment.

The ZEROe Turbofan

This is Airbus’s summary of the design.

Two hybrid hydrogen turbofan engines provide thrust. The liquid hydrogen storage and distribution system is located behind the rear pressure bulkhead.

This screen capture taken from the video, shows the plane.

This screen capture taken from the video, shows the front view of the plane.

The aircraft doesn’t look very different different to an Airbus A320 and appears to be fairly conventional. It does appear to have the characteristic tall winglets of the A 320 neo.

I don’t think the turbofan engines, that run on hydrogen will be a problem.

These could be standard turbofan engines modified to run on hydrogen, fuelled from a liquid hydrogen tank behind the rear pressure bulkhead of the fuselage.

If you want to learn more about gas turbine engines and hydrogen, read this article on the General Electric web site, which is entitled The Hydrogen Generation: These Gas Turbines Can Run On The Most Abundant Element In the Universe,

These are my thoughts of the marketing objectives of the ZEROe Turbofan.

- The cruising speed and the number of passengers are surprisingly close, so has this aircraft been designed as an A 320 or Boeing 737 replacement?

- I suspect too, that it has been designed to be used at any airport, that could handle an Airbus A 320 or Boeing 737.

- It would be able to fly point-to-point flights between most pairs of European or North American cities.

It would certainly fit the zero-carbon shorter range airliner market!

In fact it would more than fit the market, it would define it!

I very much believe that Airbus’s proposed zero-carbon hydrogen-powered designs and others like them will start to define aviation on routes of up to perhaps 3000 miles, from perhaps 2035.

- The A 320 neo was launched in December 2010 and entered service in January 2016. That was just five years and a month.

- I suspect that a lot of components like the fuselage sections, cockpit, avionics, wings, landing gear, tailplane and cabin interior could be the same in a A 320 neo and a ZEROe Turbofan.

- Flying surfaces and aerodynamics could be very similar in an A 320 neo and a ZEROe Turbofan

- There could even be commonality between the ZEROe Turboprop and the ZEROe Turbofan, with respect to fuselage sections, cockpit, avionics and cabin interior.

There also must be the possibility, that if a ZEROe Turbofan is a hydrogen-powered A 320 neo, that this would enable the certification process to be simplified.

It might even be possible to remanufacture a A 320 neo into a ZEROe Turbofan. This would surely open up all sorts of marketing strategies.

My project management, flying and engineering knowledge says that if they launched the ZEROe Turbofan this year, it could be in service by the end of the decade on selected routes.

Conclusion

Both the ZEROe Turboprop and ZEROe Turbofan are genuine zero-carbon aircraft, which fit into two well-defined market segments.

I believe that these two aircraft and others like them from perhaps Boeing and Bombardier could be the future of aviation between say 500 and 3000 miles.

With the exception of the provision of hydrogen refuelling at airports, there will be no need for any airport infrastructure.

I also wouldn’t be surprised that the thinking Airbus appear to have applied to creating the ZEROe Turbofan from the successful A 320 neo, could be applied to perhaps create a hydrogen-powered A 350.

I feel that Airbus haven’t fulling disclosed their thinking. But then no company would, when it reinvents itself.

T also think that short-haul air routes will increasing come under pressure.

The green lobby would like airlines to decarbonise.

Governments will legislate that airlines must decarbonise.

The rail industry will increasingly look to attract customers away from the airlines, by providing more competitive times and emphasising their green credentials.

Aircraft manufacturers will come under pressure to deliver zero-carbon airliners as soon as they can.

I wouldn’t be surprised to see a prototype ZEROe Turbofan or Boeing’s equivalent fly as early as 2024.

Short Term Solutions

As I said earlier, one solution is to use existing aircraft with Sustainable Aviation Fuel.

But many believe this is greenwash and rather a cop out.

So we must do better!

I don’t believe that the smaller zero- and low-carbon aircraft with a range of up to 500 miles and a capacity of around 19 seats, will be able to handle all the passengers needing to fly between and around the islands of Great Britain and Ireland.

- A Boeing 737 or Airbus A 320 has a capacity of around two hundred passengers, which would require ten times the number of flights, aircraft and pilots.

- Airports would need expansion on the airside and the terminals to handle the extra planes.

- Air Traffic Control would need to be expanded to handle the extra planes.